Unique atlases with photos. Stag beetles represent one of the most remarkable insect families, characterized by their impressive size and distinctive mandibles that have fascinated naturalists and casual observers alike. These beetles belong to the family Lucanidae, comprising over a thousand species worldwide with significant variations in size, appearance, and behavior.

Book novelties:

Prioninae of the World I., Cerambycidae of the Western Paleartic I. June Bugs,

Types of beetles insects

New E-Book: Ground Beetles, Tiger Beetles, Longhorn Beetles, Jewel Beetles, Stag Beetles, Carpet Beetles, Scarab Beetles, Rhinoceros Beetles, Weevil Beetles, Blister Beetles, Leaf Beetles, Flower Beetles,

Start Shopping, Start Saving – prices from $3 USD

Despite their sometimes intimidating appearance, particularly in males with their enlarged “antler-like” jaws, stag beetles play crucial ecological roles as decomposers and are generally harmless to humans.

Stag beetle, Lucanidae

Stag beetle questions

Lucanidae

Books about Beetles

Unique pictorial atlases for identifying Beetles:

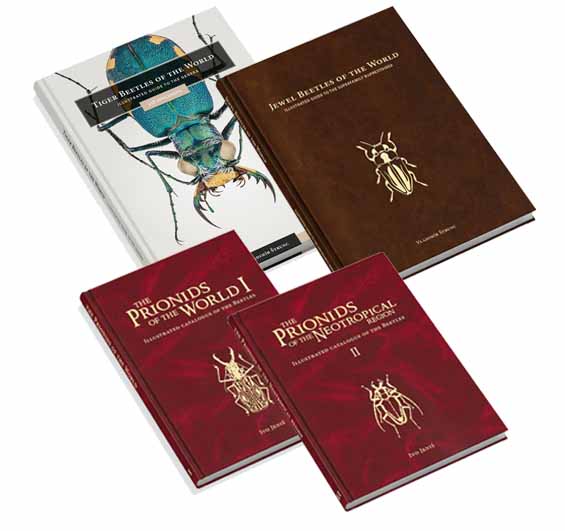

(2020) Tiger Beetles of the World, Cicindelidae, Illustrated guide to the genera

(2023) Tiger Beetles of Africa, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2024) Tiger Beetles of Orient, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2022) Ground Beetles of Africa, Afrotropical Region

(2022) Jewel Beetles of the World, Buprestidae, Illustrated guide to the Superfamily Buprestoidea

(2008) The Prionids of the World, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

(2010) The Prionids of the Neotropical region, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

Stag beetle, Lucanidae

Stag Beetles: Fascinating Giants of the Insect World

Unfortunately, many species face significant population declines due to habitat loss, forest management practices, and urbanization, leading to protected status in several countries. This report explores the biology, ecology, behavior, and conservation status of these extraordinary insects that serve as important indicators of woodland ecosystem health.

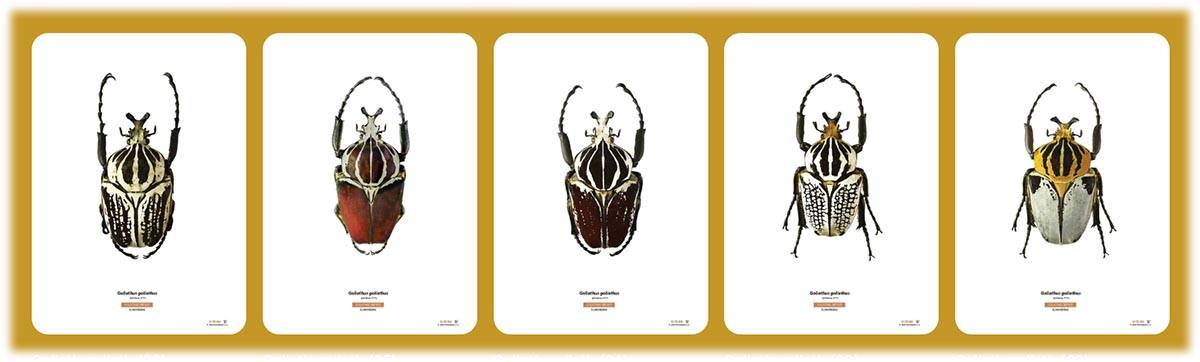

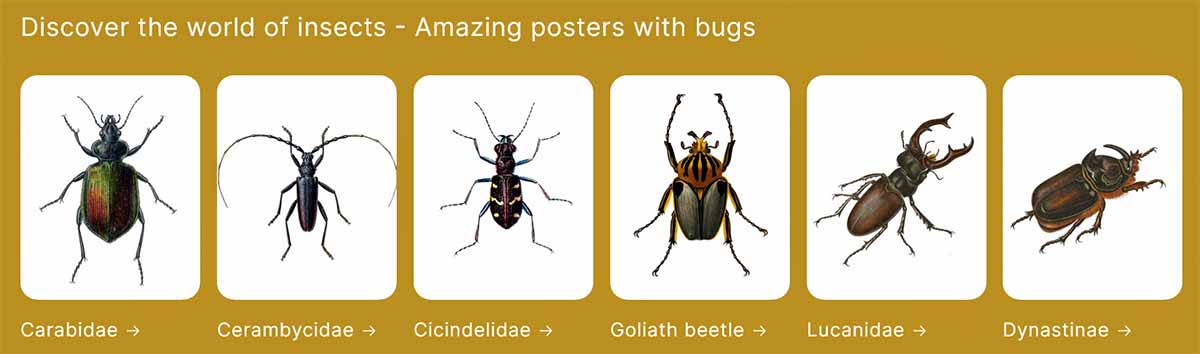

We recommend: jeweled beetles, ground beetles, tiger beetles, longhorn beetles, goliath beetle, carpet beetles

Physical Characteristics and Identification

Distinctive Features and Morphology

Stag beetles possess several unmistakable characteristics that make them among the most recognizable insects in regions where they occur. The common European stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) features a shiny black head and thorax contrasted with rich chestnut-brown wing cases, creating a striking appearance that draws immediate attention. Their strong, elongated bodies range considerably in size, from less than half an inch to nearly two and a half inches in length for adults, depending on the species. The antennae of stag beetles represent another distinctive feature, being enlarged or clubbed at the tip with segments that fan open like leaves but cannot be pressed together into a ball, containing ten segments that are often elbowed in appearance.

These specialized antennae function as sensitive sensory organs that help the beetles navigate their environment and detect potential mates or food sources. The overall appearance of these insects has earned them various colloquial names throughout history, including billywitches, oak-ox, thunder-beetles, and horse-pinchers, reflecting their cultural significance across different regions. These beetles’ robust exoskeletons and powerful legs allow them to navigate through woodland environments both on the ground and on tree trunks where they often search for sap and potential mates. Stag beetle, Lucanidae

Sexual Dimorphism

One of the most remarkable aspects of stag beetle biology is the pronounced sexual dimorphism, particularly regarding mandible development in males. Male stag beetles possess greatly enlarged, sometimes astonishing jaws that genuinely resemble the antlers of deer, which gave rise to their common name and scientific naming (Lucanus cervus refers to deer-like). These impressive mandibles serve primarily as weapons during combat with other males for mating opportunities and territory, representing a classic example of sexually selected traits that evolve specifically for reproductive competition rather than survival advantages. The size and shape of these mandibles can vary substantially even within the same species, with some male Cyclommatus mniszechi beetles being classified into distinct morphs (alpha, beta, and gamma) based on the size and position of tusk-like projections or denticles on their mandibles.

Female stag beetles, while less spectacular in their mandible development, still possess well-developed pincers that serve functional purposes in their daily activities including defense and manipulation of materials for egg-laying. Beyond their jaws, females typically appear smaller overall than their male counterparts, though they maintain the characteristic coloration and body structure of the species. This remarkable sexual dimorphism represents an evolutionary outcome of intense male competition, where larger mandibles confer advantages in combat situations that ultimately determine reproductive success.

Size Variations and Record Holders

The common European stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) holds the distinction of being the UK’s largest beetle, with adult specimens measuring up to 7.5 centimeters in length—approximately the size of an adult human’s thumb. This impressive size makes these insects particularly noticeable when they emerge during summer months, often causing surprise or concern among people unfamiliar with these harmless giants. The substantial variation in size occurs not only between species but also within species populations, with research on Cyclommatus mniszechi revealing distinct morphological groups separated by a specific switch point in mandible length at 14.01 millimeters. This size variation often correlates with behavioral differences, as larger males (termed “majors”) tend to employ different fighting strategies compared to smaller males (“minors”) of the same species, with major males more likely to escalate directly into aggressive confrontations.

The relationship between body size and mandible length follows positive allometric patterns, meaning that as body size increases, mandible size increases at an even greater rate, though the specific allometric slopes differ between major and minor males. The larvae of stag beetles can grow even larger than the adults, reaching up to 11 centimeters in length before pupation, representing a substantial size for any insect grub. While adult males display the most dramatic size variations due to their exaggerated mandibles, female size also varies considerably across and within species, reflecting genetic factors and developmental conditions during their extended larval stage.

Giraffe Stag Beetle

Miyama Stag Beetle

Stag Beetle plush

Stag Beetle price

Life Cycle and Development

Prolonged Larval Stage

Stag beetles spend the vast majority of their lifespan as larvae, with this developmental stage lasting between three to six years depending on the species and environmental conditions. After hatching from eggs laid in decaying wood, the larvae appear as white, C-shaped grubs with brownish or black heads and three pairs of legs, bearing resemblance to the larvae of scarab beetles and other related families. During this extended larval phase, the grubs feed voraciously on decaying wood and associated fungal microorganisms, gradually breaking down tough lignin and cellulose components while extracting sufficient nutrients to fuel their growth. This specialized diet allows stag beetles to occupy a specific ecological niche with limited competition from other insects, though it necessitates a prolonged developmental period to accumulate adequate nutritional reserves.

The larvae grow substantially throughout this time, eventually reaching impressive sizes before they prepare for pupation, with some species’ larvae growing up to 11 centimeters in length—larger than many adult beetles. Environmental factors significantly influence larval development rates, with periods of extremely cold weather potentially extending the process even further. Throughout this extended juvenile stage, the larvae remain hidden underground or within decomposing logs, protected from predators but vulnerable to habitat disturbance or removal of dead wood resources that form their exclusive food source and shelter.

Pupation and Metamorphosis

The transformation from larva to adult represents one of the most dramatic developmental changes in the insect world, with stag beetles undergoing complete metamorphosis within specially constructed chambers. Once a larva has completed its extended feeding period and reached full size, it leaves the rotting wood where it has been developing to construct a large protective cocoon in the surrounding soil. This cocoon, which can reach the size of an orange in larger species, provides a protected environment for the complex metamorphosis process that follows. Within this self-created chamber, the grub-like larva undergoes complete metamorphosis, a process analogous to the transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly, wherein its entire body reorganizes to form the distinctively different adult beetle with its characteristic features.

During this pupation phase, which typically lasts several weeks to months depending on temperature and other environmental factors, the developing beetle remains completely immobile and highly vulnerable to disturbance. The timing of pupation appears carefully synchronized with seasonal cycles, ensuring adult emergence coincides with appropriate weather conditions and potential mate availability. This emergence usually occurs in late spring, with most European stag beetles appearing from mid-May onwards when temperatures have sufficiently warmed to support adult activity. The successful completion of this metamorphosis represents the culmination of years of development and marks the beginning of the relatively brief adult phase focused primarily on reproduction.

Brief Adult Life and Reproductive Strategy

The adult stage of a stag beetle’s life presents a striking contrast to its prolonged larval development, with mature beetles typically surviving for only a few months despite their years-long preparation. After spending up to six years as feeding larvae, adult stag beetles generally live for just four months, emerging from their pupation chambers in late May and completing their life cycle by the end of August in European species. This brief adult phase concentrates almost entirely on reproductive activities rather than feeding or growth, with many species unable to consume solid food due to modified mouthparts specialized for different functions.

Instead, adults rely predominantly on the substantial fat reserves accumulated during their extended larval stage, supplemented by occasional feeding on tree sap from damaged trees or fallen soft fruit using their specialized feathery tongues. The short adult lifespan coincides with warm summer months, when stag beetles are most active during warm, sunny evenings, particularly in May and June when mating activities peak. Males invest significant energy in locating and competing for females, using their elaborate mandibles in ritualized combat with rival males to secure mating opportunities. Following successful mating, females return to suitable habitat areas with sufficient rotting wood to lay their eggs, often selecting the same location from which they emerged if conditions remain favorable for larval development. This reproductive strategy, with its brief but intense adult phase following years of preparation, represents an evolutionary adaptation balancing the costs of developing specialized morphology against the benefits of reproductive specialization.

Lucanidae in Africa

Habitat and Distribution

Geographic Range and Regional Variations

Stag beetles inhabit diverse regions across the globe, with different species adapted to specific geographic areas and climatic conditions. The common European stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) is distributed throughout southern and central Europe, including Britain, though notably absent from Ireland. Within Britain, these beetles show a distinct distribution pattern, being relatively widespread in southern England and inhabiting the Severn valley and coastal areas of the southwest, while becoming extremely rare or even extinct in more northern regions. This pattern reflects both historical biogeography and climatic limitations, with stag beetles generally favoring warmer temperatures than those found in northern Europe.

The genus Cyclommatus, including the species C. mniszechi studied for its fighting behavior, occupies Southeast Asian territories including southeast China, Vietnam, and northern Taiwan, where they inhabit lowland forests below approximately 750 meters in elevation. In North America, various stag beetle species occupy different ecological niches across the continent, with distribution patterns closely aligned with specific forest types and climate zones. Urban environments present unique challenges and opportunities for stag beetles, with some city parks and gardens in London providing important habitat islands that support significant populations despite surrounding development. The patchy distribution of stag beetles even within their known range often corresponds to habitat suitability and historical land use practices, with some areas maintaining healthy populations while neighboring regions show significant declines due to subtle differences in habitat quality and management.

Preferred Environments and Microhabitats

Stag beetles demonstrate clear preferences for specific habitat types, generally favoring environments with abundant dead wood resources essential for their reproduction and development. These beetles typically inhabit woodland edges, hedgerows, traditional orchards, parks, and gardens where sufficient decaying woody material is available for egg-laying and larval development. Oak woodlands represent particularly important habitat for many stag beetle species, with the common European stag beetle showing a strong association with these ecosystems that provide both food resources and suitable breeding sites.

The beetles require a complex matrix of microhabitats within these broader environments, including standing dead trees, fallen logs in various stages of decay, and underground root systems that support different life stages and activities. During breeding seasons, adult stag beetles can be found on the trunks and branches of trees where they seek sap runs for feeding and potential mates, particularly focusing on damaged areas where sap flows freely. In Taiwan, Cyclommatus mniszechi beetles have been observed breeding specifically on various broadleaf trees including Fraxinus griffithii, Broussonetia papyrifera, Citrus species, and Koelreuteria elegans, demonstrating specialized host tree preferences. The soil characteristics surrounding decaying wood also influence habitat suitability, as females need appropriate substrate for constructing egg chambers and larvae require soil conditions that support cocoon formation without excessive moisture or dryness. The common thread across these diverse environments is the presence of decaying wood in multiple stages of decomposition, providing the continuous resources needed for overlapping generations of these long-lived insects.

Urban Habitats and Adaptation

Despite their association with woodland environments, several stag beetle species have demonstrated remarkable adaptability to urban and suburban settings where suitable microhabitats remain available. In southern England, including London parks and gardens, stag beetles maintain significant populations when dead wood resources are preserved through conscious conservation efforts. Urban gardens with log piles, tree stumps, and older wooden fence posts can provide crucial habitat islands within developed landscapes, supporting complete stag beetle life cycles despite surrounding urbanization. The adaptation to urban environments includes behavioral modifications, with some populations showing increased nocturnal activity to avoid human disturbance and higher temperatures during daytime hours. Research has found that stag beetles in urban settings may utilize novel microhabitats, including deep layers of hardwood mulch used in hiking trails and playgrounds when natural dead wood is scarce.

These adaptations demonstrate considerable ecological flexibility despite the beetles’ specialized requirements. The attraction of adult stag beetles to artificial lights at night represents another aspect of urban adaptation, though this behavior potentially increases vulnerability to predation and vehicle collisions. Conservation initiatives in urban areas increasingly recognize the importance of maintaining “stag beetle friendly” spaces with retained dead wood features, creating connected habitat networks across urban landscapes. The success of stag beetles in some urban environments offers encouraging evidence that thoughtful landscape management can support biodiversity even within human-dominated settings, though these urban populations remain vulnerable to habitat changes and development pressures that could eliminate critical resources required for complete life cycles.

Behavior and Ecology

Specialized Feeding Adaptations

Stag beetles exhibit specialized feeding behaviors that change dramatically between their larval and adult stages, reflecting their ecological adaptations. During their extended larval phase, stag beetles consume decaying wood and the associated fungal microorganisms, functioning as important decomposers in forest ecosystems. These wood-eating grubs possess specialized gut microbiota that assist in breaking down tough cellulose and lignin compounds, enabling them to extract nutrients from this challenging food source over their multi-year development. Upon reaching adulthood, most stag beetle species undergo a substantial dietary shift, with many species unable to consume solid food due to modified mouthparts specialized for different functions.

Adult beetles primarily feed on tree sap at points where branches or bark have been damaged, using their specialized feathery tongues to drink these nutrient-rich fluids without causing additional harm to living trees. Some species supplement this diet with rotting fruit or the sweet secretions of aphids known as honeydew, particularly when tree sap sources are limited. The dramatic transition from wood-consuming larvae to sap-feeding adults reflects the different ecological roles these insects play throughout their life cycle. For many stag beetle species, adults rely heavily on fat reserves accumulated during the larval stage, using these stored resources to fuel their reproductive activities during their relatively brief adult lifespan. This specialized nutritional strategy allows stag beetles to exploit different resource niches throughout their life cycle while minimizing competition with other insect species that utilize similar but not identical resources.

Combat and Mating Behavior

Male stag beetles engage in remarkable combat behaviors using their enlarged mandibles, competing for access to females and resources in complex ritualized contests. These battles between males truly resemble the fighting of male deer or elk (hence the name “stag” beetles), with contestants using their antler-like jaws to wrestle opponents in tests of strength rather than inflicting serious injury. Research on Cyclommatus mniszechi has revealed sophisticated fighting strategies that progress through observable sequences, beginning with initial contact and defensive posturing before potentially escalating to pushing, attacking, and ultimately tussling with interlocked mandibles. Different morphological types display distinct behavioral patterns during these contests, with larger “major” males more likely to escalate directly into aggressive phases while smaller “minor” males tend to progress more gradually through combat stages and remain longer within particular phases.

These differences suggest that body size and weapon size influence fighting strategies, with larger males potentially having more to gain and less to lose in aggressive confrontations. After initial touching and defensive posturing, contests may progress to body raising with rapid antennal movement, pushing with raised mandibles, attacking by biting with mandibles, and ultimately tussling by interlocking mandibles and pushing against each other. From these tussles, winners often secure victory by clamping onto the head or body of their opponent before flipping them away, demonstrating the functional advantage of larger mandibles in securing favorable positions during combat. These complex behavioral sequences represent sophisticated examples of ritualized animal combat that minimizes serious injury while effectively determining competitive outcomes based on size, strength, and fighting ability.

Ecological Significance and Ecosystem Services

Stag beetles fulfill crucial ecological functions within their habitats, contributing significantly to forest ecosystem health and biodiversity through several important mechanisms. As saproxylic insects (those dependent on dead or decaying wood), they serve as nature’s recyclers, breaking down woody plant material that would otherwise accumulate in forest environments. The extended larval feeding on decaying wood accelerates decomposition processes, releasing nutrients locked in dead trees and returning them to the soil for use by living plants, completing important nutrient cycles in woodland ecosystems. Through their tunneling and feeding activities, stag beetle larvae create microhabitats utilized by numerous other organisms, from fungi and microbes to other invertebrates that follow in the ecological succession of decaying wood.

The consumption and fragmentation of dead wood by stag beetle larvae increases surface area for microbial activity, accelerating overall decomposition rates beyond what would occur without their presence. Adult stag beetles contribute to different ecological processes, potentially acting as pollinators when visiting flowers and trees for sap, and serving as important food sources for various predators including bats, birds, and insect-eating mammals. The presence of stag beetles in an ecosystem often indicates good habitat quality and connectivity, as these insects require specific conditions and sufficient dead wood resources to complete their life cycle, making them valuable bioindicators for conservation assessment. Their lengthy life cycle ensures continuous decomposition activity across seasons and years, providing stability to woodland decomposition processes despite seasonal fluctuations in environmental conditions. The ecological services provided by stag beetles, though often overlooked, represent important contributions to forest ecosystem functioning and resilience in the face of environmental changes.

Conservation Status and Threats

Population Trends and Monitoring Challenges

Stag beetle populations have exhibited concerning declines across various parts of their range, though comprehensive assessment remains challenging due to their cryptic habits and extended life cycle. In many European regions, particularly in the northern parts of their range, stag beetles have experienced significant population reductions, with some areas witnessing local extinctions. The common European stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) is now considered extremely rare or extinct in northern parts of Britain, while maintaining stronger populations in southern England. Monitoring population trends presents considerable methodological challenges, as the majority of each beetle’s life span occurs underground as larvae, hidden from conventional survey methods.

Adult emergence can fluctuate naturally from year to year based on environmental conditions, requiring long-term monitoring programs to distinguish between natural population cycles and genuine declines. Citizen science initiatives have improved monitoring in some regions, engaging public participants in recording adult beetle sightings during summer months when they are most visible. These programs have revealed important information about distribution patterns while simultaneously raising public awareness about conservation needs. Anecdotal evidence from naturalists and long-term residents in many areas suggests substantial declines over recent decades, corresponding with increased urbanization and changes in woodland management practices that reduce dead wood availability. The combination of formal scientific surveys and citizen science approaches provides complementary data that helps conservation biologists assess population status and identify priority areas for protection efforts. Despite these advances in monitoring methodology, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding population dynamics, dispersal patterns, and genetic structure of many stag beetle populations, highlighting the need for continued research to inform effective conservation strategies.

Habitat Loss and Modern Land Management

Habitat loss and fragmentation represent the most significant threats to stag beetle populations globally, with several human activities contributing to the degradation of suitable environments for these specialized insects. The development of open spaces in urban and suburban areas has eliminated many potential habitats, reducing the available territory for stag beetles to complete their life cycle. Modern forestry and gardening practices that prioritize “tidiness” by removing dead wood and stumps directly eliminate crucial resources for egg-laying females and developing larvae, often motivated by aesthetic preferences that fail to recognize the ecological value of decomposing wood. The replacement of native broadleaf woodlands with conifer plantations in many regions has reduced habitat suitability, as many stag beetle species show strong preferences for specific deciduous tree species that provide appropriate wood quality and decomposition characteristics.

Fragmentation of woodland habitats through development and agricultural expansion creates isolated populations with limited genetic exchange, potentially reducing long-term viability and resilience to environmental changes through decreased genetic diversity. The extended development period of stag beetles makes them particularly vulnerable to habitat disturbance, as activities that remove decaying wood can eliminate entire generations of developing larvae before they reach adulthood. Climate change presents an additional threat through altering phenological patterns and potentially disrupting the synchronization between beetle life cycles and environmental conditions, though some species may benefit from warming temperatures in the northern parts of their range. The combined effects of these threats create significant conservation challenges requiring integrated approaches that address both immediate habitat protection and longer-term landscape connectivity to ensure viable stag beetle populations persist into the future.

Conservation Strategies and Public Engagement

Conservation initiatives for stag beetles have expanded in recent years, combining public awareness campaigns with practical habitat management approaches to protect these charismatic insects. In several European countries, stag beetles have received protected species status, limiting collection and creating legal frameworks for habitat conservation. Organizations like the People’s Trust for Endangered Species in the UK have established dedicated stag beetle conservation programs, including citizen science monitoring projects that engage the public in recording beetle sightings to better understand distribution patterns and population trends. Educational outreach emphasizes the harmless nature of these impressive insects despite their sometimes intimidating appearance, helping to transform public perception from fear to appreciation of their ecological importance. Management guidelines for woodland owners and gardeners now frequently include recommendations for retaining dead wood in situ and creating habitat piles when trees are felled or pruned, providing practical actions that individuals can take to support stag beetle conservation.

Urban planning in some regions has begun incorporating stag beetle conservation considerations, preserving important habitat areas within development plans and creating “stepping stone” habitats to maintain population connectivity across fragmented landscapes. Research efforts continue to expand our understanding of stag beetle ecology and behavior, with studies of fighting behavior and mandible morphology providing insights into evolutionary processes while simultaneously informing conservation strategies tailored to specific species and regional conditions. Community involvement represents a crucial aspect of successful conservation work, transforming public perception of these sometimes intimidating-looking insects into appreciation for their ecological roles and unique adaptations. Despite these positive initiatives, continued vigilance and expanded conservation efforts remain necessary to ensure the long-term survival of diverse stag beetle populations in an increasingly human-modified world.

Conclusion, Stag beetle, Lucanidae

Stag beetles represent remarkable examples of insect diversity and adaptation, with their distinctive morphology, complex life cycles, and important ecological functions making them significant components of woodland ecosystems worldwide. From their impressive sexually dimorphic mandibles to their extended underground larval development, these beetles have evolved specialized traits that enable them to occupy specific ecological niches while fulfilling vital roles in wood decomposition and nutrient cycling.

The dramatic differences between males and females highlight the power of sexual selection in shaping morphological evolution, with male combat behaviors driving the development of elaborate weapons that serve both as fighting tools and visual signals. Their remarkably long life cycle, with up to six years spent as developing larvae followed by just a few months as reproductive adults, demonstrates a fascinating evolutionary strategy that prioritizes substantial investment in development to support brief but intense reproductive activity. The conservation challenges facing many stag beetle species reflect broader environmental issues affecting woodland biodiversity globally, particularly habitat loss, fragmentation, and management practices that reduce dead wood availability in both natural and urban environments.

Public engagement in stag beetle conservation offers promising avenues for population recovery, combining scientific research with citizen participation to monitor trends and protect critical habitats. The future of stag beetle conservation will require continued collaboration between researchers, land managers, policymakers, and the public to ensure these fascinating insects maintain healthy populations across their natural range. By preserving dead wood resources, maintaining connectivity between habitat patches, and raising awareness of these beetles’ ecological importance, conservation efforts can support not only stag beetles but also the countless other organisms that depend on similar woodland microhabitats. Understanding and appreciating the biology and ecological significance of stag beetles provides valuable insights into the intricate relationships that sustain forest ecosystems and the contributions of invertebrate species to environmental health and biodiversity conservation. Stag beetle, Lucanidae

Stag beetles, belonging to the family Lucanidae, are among the most fascinating coleopterans due to their distinct morphology and life cycle. Their stag beetle life cycle follows a 4 stage life cycle insects pattern, transitioning from egg, stag beetle larvae, pupa, and finally to adulthood. Unlike 3 stage life cycle insects, which undergo incomplete metamorphosis, stag beetles belong to the 5 stages of insect development, as their growth includes extended larval phases.

The stag beetle species list includes a variety of taxa, such as the giant stag beetle, Japanese stag beetle, rainbow stag beetle, and Miyama stag beetle. The lesser stag beetle scientific name and the Miyama stag beetle scientific name help in taxonomic classification. The Miyama stag beetle white eyes variant is particularly rare, with the Miyama stag beetle white eyes price being significantly higher in niche markets.

For collectors, various species are available, with the stag beetle for sale USA and stag beetle for sale Nigeria markets catering to enthusiasts. The stag beetle price in USA, stag beetle price in Nigeria, and stag beetle price in dollar depend on species rarity. Some of the most sought-after beetles include the giant stag beetle for sale, giraffe stag beetle for sale, and rainbow stag beetle for sale, with the rainbow stag beetle price being particularly high due to its unique coloration.

One common question is, “Can you sell stag beetles?” The answer varies by region, as regulations govern wildlife trade. Similarly, people often ask, “How to sell stag beetle?”, especially if they are breeding them. In the gaming world, the giraffe stag beetle Animal Crossing species is highly valued, and in Twilight Princess, the female stag beetle Twilight Princess is a notable in-game collectible.

In terms of behavior and safety, many wonder, “Can stag beetles hurt you?”, “Do stag beetle bites hurt?”, and “Are stag beetle bites dangerous?” While males have large mandibles, they are primarily used for combat rather than biting humans. However, the female stag beetle bite can be slightly more painful due to their stronger jaws. Contrary to common fears, stag beetles are not poisonous, and despite misconceptions, they are not inherently dangerous or harmful.

For those interested in keeping them as pets, the debate over “Are stag beetles good pets?” and “Are stag beetles bad?” arises. While they are fascinating creatures, their care requires knowledge of their stag beetle diet, which consists of tree sap and soft fruits. Proper stag beetle larvae care is essential, as they remain in the larval stage for several years before pupation. The process of stag beetle larvae identification is crucial for breeders to distinguish between different species at an early stage.

The longevity of these beetles varies; for example, the giant stag beetle lifespan differs from the rainbow stag beetle lifespan due to environmental and genetic factors. Stag beetles provide ecological stag beetle benefits by aiding in the decomposition of decaying wood, making them essential for forest ecosystems.

The rarity of these beetles often leads to questions like “How rare are stag beetles?”, as some populations are in decline. This raises concerns such as “Are giant stag beetles dangerous?” and “Are stag beetles endangered?”. While some species are thriving, others are at risk due to habitat destruction. Understanding where are stag beetles found and protecting their stag beetle habitat is crucial for conservation.

In terms of commercial value, the female stag beetle price and giraffe stag beetle price fluctuate based on demand. The Miyama stag beetle price is particularly high due to its exotic appeal. In some markets, stag beetle plush toys have become popular among enthusiasts.

A key area of entomological study involves the stag beetle larvae stages, which are comparable to the stick insect life cycle stages. However, unlike the life stages of a hemimetabolous insect, stag beetles undergo a complete metamorphosis, making them more similar to holometabolous insects.

Ultimately, stag beetles remain an important subject in entomology, as highlighted in various stag beetle books. Understanding their classification, ecological role, and care requirements helps ensure their continued survival in both natural and captive environments.

-

Types of beetles insects€ 13.00

Types of beetles insects€ 13.00 -

Tiger Beetles of Orient€ 129.00

Tiger Beetles of Orient€ 129.00 -

Tiger Beetles of Africa€ 129.00

Tiger Beetles of Africa€ 129.00 -

The Prionids of the WorldProduct on sale€ 39.00

The Prionids of the WorldProduct on sale€ 39.00 -

Ground Beetles of Africa (2nd edition)€ 136.00

Ground Beetles of Africa (2nd edition)€ 136.00 -

Jewel Beetles of the World€ 105.00

Jewel Beetles of the World€ 105.00 -

Tiger Beetles of the World€ 109.00

Tiger Beetles of the World€ 109.00 -

The Prionids of the Neotropical regionProduct on sale€ 59.00

The Prionids of the Neotropical regionProduct on sale€ 59.00