Lepidoptera, commonly known as butterflies and moths, is one of the most diverse and widespread orders of insects, comprising approximately 180,000 species worldwide. This order is characterized by the presence of scales on their wings, which are responsible for their vibrant colors and patterns. The name “Lepidoptera” is derived from the Greek words “lepido,” meaning scale, and “ptera,” meaning wing.

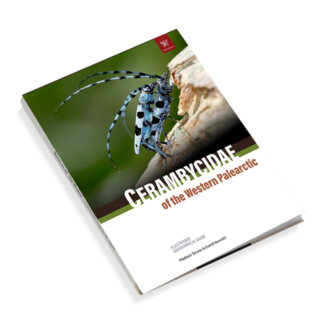

Book novelties:

Prioninae of the World I.

Cerambycidae of the Western Paleartic I.

Order Lepidoptera, Insect

Book about Beetles

Buy now. List of family Coleoptera

You can find here: Carabidae, Buprestidae, Cerambycidae, Cicindelidae, Scarabaeidae, Lucanidae, Chrysomelidae, Curculionidae, Staphylinidae

Books about Beetles

Lepidoptera

Order Lepidoptera, Insect

The order Lepidoptera is further divided into two main suborders: Rhopalocera (butterflies) and Heterocera (moths). Butterflies are typically diurnal, exhibiting bright colors and slender bodies, while moths are generally nocturnal, often possessing more muted colors and robust bodies. This distinction is not only morphological but also behavioral, with butterflies often engaging in elaborate courtship displays and moths relying on pheromones for mate attraction.

Conservation of Lepidoptera species is of increasing concern due to habitat loss, climate change, and pesticide use. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), approximately 10% of butterfly species are currently threatened with extinction. Conservation efforts are essential to preserve these species, as they are indicators of environmental health and contribute significantly to ecosystem services.

Books about Beetles

Unique pictorial atlases for identifying Beetles:

(2020) Tiger Beetles of the World, Cicindelidae, Illustrated guide to the genera

(2023) Tiger Beetles of Africa, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2024) Tiger Beetles of Orient, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2022) Ground Beetles of Africa, Afrotropical Region

(2022) Jewel Beetles of the World, Buprestidae, Illustrated guide to the Superfamily Buprestoidea

(2008) The Prionids of the World, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

(2010) The Prionids of the Neotropical region, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

Conclusion about Lepidoptera

Order Lepidoptera, Insect

In conclusion, Lepidoptera is a vital order of insects that encompasses a wide variety of species with significant ecological roles. Understanding their biology, behavior, and conservation status is crucial for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem stability. Continued research and education on this fascinating group will aid in their preservation and the health of the environments they inhabit.

Order Lepidoptera: A Comprehensive Overview of Moths and Butterflies

Lepidoptera, comprising moths and butterflies, represents one of the most diverse insect orders, accounting for nearly 10% of all known animal species with approximately 160,000 described species worldwide. This remarkable order is characterized by the presence of scales on wings and body parts, a feature reflected in its name derived from Greek terms for “scale” and “wings.” The taxonomic structure includes 43 superfamilies organized across multiple suborders, with the bulk of species contained within the suborder Glossata. Recent genetic research has identified 217 unique gene families that emerged during early lepidopteran evolution, including novel transporters potentially linked to diverse feeding behaviors and unusual propeller-shaped proteins likely acquired through horizontal gene transfer from bacteria. The fossil record, though less extensive than other insect orders, comprises 4,593 known specimens with a notable bias toward the late Paleocene to middle Eocene period, providing valuable insights into the evolutionary timeline of this significant insect group.

Taxonomic Classification and Diversity

Etymology and Historical Classification

The term “Lepidoptera” etymologically stems from the Latin prefix “lepido-” meaning scales, combined with the ancient Greek terms “lepis” (scales) and “pteron” (wings), collectively referring to the distinctive scale-covered wings characteristic of this order. The pioneering taxonomist Linnaeus established an early classification system that divided these insects into three primary groups: butterflies, skippers, and moths (both micro-moths and macro-moths). This initial classification has evolved considerably since then, but the fundamental distinction between the primarily day-flying butterflies and largely nocturnal moths remains a useful, if somewhat simplified, conceptual division.

While there is no universally recognized common name encompassing all members of Lepidoptera, the scientific study of this order has developed into a specialized field, with those who collect or study these insects professionally being known as lepidopterists. The order’s diversity is remarkable, with Lepidoptera accounting for approximately 10% of all identified living organisms. In terms of species richness, it stands second only to Coleoptera (beetles) among insect orders, highlighting its evolutionary success and ecological adaptability across global ecosystems.

Modern Taxonomic Structure

The modern taxonomic organization of Lepidoptera reflects a complex evolutionary history. The order is divided into several suborders, with the majority of species contained within the suborder Glossata. The taxonomic hierarchy begins with basal groups comprising relatively few families and species, followed by increasingly diverse lineages. The bulk of lepidopteran diversity is concentrated in the infraorder Heteroneura within the Glossata suborder.

At the highest levels, the taxonomic structure includes:

Suborder Zeugloptera (including the superfamily Micropterigoidea)

Suborder Aglossata (including the superfamily Agathiphagoidea)

Suborder Heterobathmiina (including the superfamily Heterobathmioidea)

Suborder Glossata (containing the vast majority of lepidopteran species)

Within Glossata, further subdivisions include the infraorders Dacnonypha, Acanthoctesia, Lophocoronina, Neopseustina, Exoporia, and the extremely diverse Heteroneura. This taxonomic framework organizes approximately 126 families and 46 superfamilies, though the exact numbers may vary slightly between different classification systems.

Diversity and Distribution

Lepidoptera exhibits extraordinary diversity, with current estimates indicating approximately 180,000 species divided among 128 families and 47 superfamilies. More specifically, researchers have documented about 70,820 butterfly species, 3,700 skipper species, and approximately 165,000 moth species (including both micro-moths and macro-moths). However, it should be noted that new species continue to be discovered, making these figures dynamic rather than definitive.

The evolutionary success of Lepidoptera is demonstrated by their presence in virtually all terrestrial ecosystems worldwide. Their adaptation to diverse ecological niches reflects remarkable evolutionary plasticity, particularly regarding feeding behaviors and defensive strategies. The earliest lepidopterans are thought to have emerged in the Late Carboniferous period, roughly 300 million years ago, and were likely pollen feeders. A significant evolutionary development occurred in the Middle Triassic (approximately 240 million years ago) with the evolution of the tube-like proboscis that enabled nectar feeding, coinciding with the rise of flowering plants. This co-evolutionary relationship with angiosperms has been a key driver of lepidopteran diversification and ecological specialization throughout their evolutionary history.

Morphology and Life Cycle

External Morphology

The external morphology of Lepidoptera is distinctive and characterized primarily by the presence of scales covering both the body and appendages, particularly the wings. These scales, which give butterflies and moths their characteristic appearance and often vibrant coloration, represent a defining characteristic of the order. Lepidopteran species vary dramatically in size, ranging from microlepidoptera measuring just a few millimeters to impressive specimens with wingspans of several inches, such as the Atlas moth.

The adult lepidopteran body consists of three primary regions: head, thorax, and abdomen. The head is structured like a capsule with various appendages emerging from it, most notably the proboscis formed from modified maxillary galeae, which is adapted for nectar feeding in most species. The thorax bears three pairs of legs and typically two pairs of wings, though wing structure varies considerably across different families. The abdomen is less heavily sclerotized (hardened) compared to the head and thorax, allowing for flexibility. While most adult Lepidoptera possess a prominent proboscis for nectar feeding, some non-feeding adult species display reduced mouthparts, and others have mouthparts modified for piercing fruits or, rarely, for blood feeding.

Developmental Stages

Lepidoptera undergo complete metamorphosis (holometabolous development), progressing through four distinct life stages: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis in butterflies), and adult (imago). This developmental pattern represents one of the most dramatic transformations in the animal kingdom, with each stage adapted for different ecological functions and survival strategies.

The larval stage, commonly known as the caterpillar, serves primarily as the feeding and growth phase. Caterpillars possess a sclerotized head capsule with chewing mouthparts, three pairs of true legs on the thoracic segments, and typically up to five pairs of prolegs on the abdominal segments. Most caterpillars are herbivorous, though some species have evolved carnivorous habits, feeding on ants, aphids, or even other caterpillars. Growth occurs through a series of molts (ecdysis), with each developmental stage between molts referred to as an instar. This process is regulated by hormonal changes that trigger the shedding of the old exoskeleton to accommodate increasing body size.

The pupal stage represents a remarkable transformation period during which the larval tissues are extensively reorganized to form adult structures. Many moths create protective silk cocoons within which pupation occurs, while butterfly pupae (chrysalides) are often suspended from a cremaster, a hook-like structure at the posterior end. During this seemingly dormant phase, complex internal reorganization processes create the adult form.

Distinguishing Features

Several key features distinguish Lepidoptera from other insect orders. Perhaps most characteristic are the scales covering the wings and body, which are modified flattened setae (hairs) that provide various functions including coloration, thermoregulation, and in some cases, pheromone dispersal. Wing venation patterns and structure also serve as important taxonomic characters, varying systematically across different lepidopteran groups.

Mouthpart structure represents another significant distinguishing feature. Primitive lepidopteran families (such as Micropterigidae) retain functional mandibles as adults, similar to their evolutionary ancestors. However, the vast majority of Lepidoptera possess a coiled proboscis formed from modified maxillary galeae, specialized for liquid feeding. When not in use, this proboscis is typically kept coiled beneath the head, but it extends when the insect feeds on nectar or other liquid food sources.

The antennae of Lepidoptera show remarkable diversity in form, ranging from filiform (thread-like) to highly complex structures such as the feathery (plumose) antennae found in many moth families. These sensory structures are especially important for mate location, with males of many species possessing more elaborate antennae than females due to their role in detecting female sex pheromones over considerable distances.

Evolutionary History and Genetics

Phylogenetic Relationships

Lepidoptera forms a monophyletic group strongly supported by numerous synapomorphies (shared derived characteristics). Within the broader insect evolutionary tree, Lepidoptera shares a well-established sister-group relationship with Trichoptera (caddisflies), with these two orders together constituting the taxon Amphiesmenoptera. This relationship is supported by multiple morphological and molecular lines of evidence. The Amphiesmenoptera, in turn, forms part of the Mecopterida or “panorpoid” clade within Endopterygota, alongside Antliophora (which includes Mecoptera, Siphonaptera, and Diptera).

The internal phylogenetic structure of Lepidoptera has been extensively studied, with the most basal lineages (such as Micropterigidae) retaining primitive features like functional mandibles in adults. These ancient lineages comprise relatively few species, with the vast majority of lepidopteran diversity concentrated in more derived groups, particularly within the Glossata suborder. The evolution of a coiled proboscis in ancestral Glossata represented a key innovation, enabling exploitation of liquid food resources and likely contributing significantly to subsequent diversification.

Fossil Record

The lepidopteran fossil record, while less extensive than that of some other insect orders, provides valuable insights into the group’s evolutionary history. Current documentation includes 4,593 known fossil specimens, comprising 4,262 body fossils and 331 trace fossils. Analysis of this fossil record reveals a significant temporal bias, with most specimens dating to the late Paleocene through middle Eocene interval (approximately 56-40 million years ago). This bias likely reflects both preservation conditions favorable to fossilization during this period and the increasing diversity of the order following the evolution of key adaptations.

The earliest definitive lepidopteran fossils date to the Late Carboniferous period (approximately 300 million years ago), though these ancient forms would have differed considerably from modern representatives. The fossil record indicates that early lepidopterans were likely pollen feeders with mandibulate mouthparts similar to those retained in the extant family Micropterigidae. The evolution of the distinctive proboscis structure that characterizes most modern Lepidoptera occurred later, during the Middle Triassic period (around 240 million years ago), coinciding with the diversification of flowering plants.

Genetic Innovations

Recent genomic research has provided unprecedented insights into the genetic basis of lepidopteran evolution. A comprehensive comparative genomic study of 115 insect species, including 99 Lepidoptera, identified 217 gene families (orthogroups) that emerged on the branch leading to Lepidoptera. Of these novel gene families, 177 likely originated through gene duplication followed by extensive sequence divergence, 2 are candidates for horizontal gene transfer, and 38 have no known homology outside Lepidoptera, suggesting possible de novo genesis.

Two particularly significant novel gene families have been identified that are conserved across all lepidopteran species and underwent substantial duplication, indicating important roles in lepidopteran biology. The first encodes a family of sugar and ion transporter molecules, potentially involved in the evolution of diverse feeding behaviors characteristic of early Lepidoptera. The second, named “propellin,” encodes unusual propeller-shaped proteins that likely originated through horizontal gene transfer from Spiroplasma bacteria.

These genetic innovations highlight the importance of both gene duplication and horizontal gene transfer in generating the genetic novelty that underlies the remarkable morphological and ecological diversity of Lepidoptera. The continued retention and further duplication of these novel gene families across all lepidopteran lineages suggests their fundamental importance to the biology and evolutionary success of the order.

Ecological Significance and Conservation

Ecological Roles

Lepidoptera play vital ecological roles across terrestrial ecosystems worldwide. As predominantly herbivorous insects, caterpillars serve as primary consumers in food webs, converting plant biomass into animal protein. This function makes them important conduits for energy flow through ecosystems. Additionally, both larvae and adults serve as crucial food sources for numerous predators, including birds, bats, small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrate predators such as spiders and predatory insects.

Perhaps the most ecologically significant role of adult Lepidoptera involves pollination. The evolution of the proboscis enabled exploitation of floral nectar resources, establishing butterflies and moths as important pollinators for many plant species. This has led to intricate co-evolutionary relationships, with some plant species developing specialized floral structures accessible only to specific lepidopteran pollinators with appropriately shaped proboscides. Such specialized relationships highlight the ecological interdependence between Lepidoptera and their plant hosts.

While most Lepidoptera provide beneficial ecological services, certain species function as agricultural and forestry pests. Families such as Noctuidae (owlet moths), Geometridae (worm moths), and Pyralidae contain numerous economically significant pest species whose caterpillars can cause substantial damage to crops, stored products, and forest trees. This agricultural impact has made certain lepidopteran families the subject of extensive research in applied entomology and pest management.

Conservation Status and Efforts

Many Lepidoptera species face significant conservation challenges due to habitat loss, climate change, pesticide use, and other anthropogenic factors. Recognition of these threats has led to the establishment of monitoring and conservation initiatives specifically focused on Lepidoptera. The Lepidoptera Conservation Bulletin (LCB), produced by Butterfly Conservation, represents one such effort, documenting diverse conservation work carried out for moths and butterflies in the United Kingdom.

This annual publication summarizes conservation activities and research advances regarding UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Species of both butterflies and moths, including information on distribution, habitat requirements, and management practices. The bulletin serves multiple purposes, providing feedback to data contributors while also creating a valuable repository of information for conservation practitioners. It uniquely compiles both published scientific literature and the “grey literature” of conservation reports that might otherwise remain difficult to access.

Conservation efforts for Lepidoptera typically involve habitat protection and management, species monitoring through systematic surveys, captive breeding programs for particularly threatened species, and public education initiatives. These activities reflect growing recognition of Lepidoptera as both ecologically important organisms and valuable bioindicators of environmental health, whose population trends can signal broader ecosystem changes.

Conclusion Order Lepidoptera, Insect

The Order Lepidoptera represents one of the most successful and diverse insect lineages, having evolved an extraordinary range of adaptations that have enabled colonization of virtually all terrestrial ecosystems. From their distinctive scaled wings to their complete metamorphosis and specialized feeding structures, Lepidoptera exhibit numerous innovations that have contributed to their evolutionary success. The taxonomic complexity of the order reflects its long evolutionary history, with primitive lineages retaining ancestral features alongside highly derived groups displaying sophisticated adaptations.

Recent advances in genomic research have begun to illuminate the genetic underpinnings of lepidopteran evolution, identifying novel gene families that likely played crucial roles in the development of key adaptations. Meanwhile, the fossil record, despite its limitations, provides temporal context for understanding the group’s evolutionary timeline, particularly regarding the development of the proboscis and co-evolution with flowering plants. These complementary approaches are enhancing our understanding of how Lepidoptera achieved their remarkable diversity. Lepidoptera

Conservation concerns affecting many lepidopteran species highlight the vulnerability of even such successful organisms to anthropogenic threats. Continued research and monitoring efforts will remain essential for preserving lepidopteran diversity and the ecological functions these insects provide. As studies of Lepidoptera advance, integrating morphological, ecological, paleontological, and genomic approaches, our understanding of this fascinating insect order will continue to deepen, potentially revealing new insights into fundamental evolutionary processes and patterns of biodiversity.