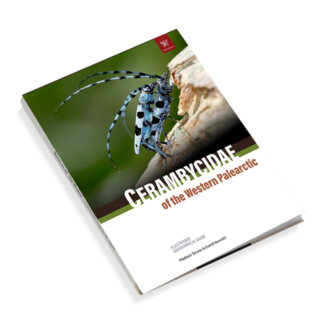

Longhorn Beetles, Cerambycidae:

Biology, Ecology, and Natural History

Taxonomic Position: Order Coleoptera, Superfamily Chrysomeloidea, Family Cerambycidae

Common Names: Longhorn beetles, longicorn beetles, round-headed borers, capricorn beetles

Species Diversity: Approximately 35,000-40,000 described species in over 4,000 genera

Geographic Range: Worldwide distribution in all terrestrial biogeographic regions

Titanus giganteus

Main Features

Longhorn beetles (family Cerambycidae) constitute one of the largest and most diverse families within the order Coleoptera, rivaling even the extraordinarily speciose weevils (Curculionidae) in taxonomic richness. The family is characterized by typically elongate antennae that often exceed body length, giving rise to the common name “longhorn.” These beetles play crucial ecological roles as decomposers of dead wood and herbivores on living plants, with larvae of most species developing within woody plant tissues. The family includes both ecologically beneficial decomposers and economically significant forest and timber pests.

The defining characteristic of cerambycid beetles is the elongate, multisegmented antennae that in many species exceed body length and may be several times longer than the body in extreme cases. These antennae arise from prominent antennal tubercles or emarginations in the compound eyes, creating the distinctive head profile characteristic of the family. Antennal length and structure vary considerably among subfamilies and genera, with some groups having relatively short antennae while others possess spectacularly elongate, often setose antennae that curve gracefully backward over the body.

Size variation within Cerambycidae is extreme, spanning more than two orders of magnitude from tiny species of 2-3 mm total length to giants exceeding 170 mm. The largest species, Titanus giganteus from South America, ranks among the longest beetles in the world. This remarkable size variation reflects diverse evolutionary trajectories and ecological adaptations across the family’s global distribution and taxonomic breadth.

Morphologically, longhorn beetles exhibit typical coleopteran features including hardened elytra, membranous hindwings, and well-developed legs. The body form ranges from robust and cylindrical to flattened or elongate and linear, reflecting adaptations to different ecological niches and wood-boring lifestyles. Coloration is extremely diverse, from cryptic browns and grays to brilliant metallic colors, complex patterns, and aposematic color combinations warning of chemical defenses or mimicking other organisms.

The vast majority of cerambycid species are wood-borers as larvae, developing within dead or living woody tissues. This fundamental ecological role as xylophages (wood-feeders) unites the family and distinguishes them from most other beetle groups. Adults are typically free-living and may feed on flowers, pollen, bark, leaves, or other plant materials, though some species do not feed as adults. The combination of wood-boring larvae and often flower-visiting adults makes longhorn beetles important components of forest ecosystems.

Coleoptera

-

The Prionids Collection Bundle

Product on sale

€ 59.00

The Prionids Collection Bundle

Product on sale

€ 59.00

-

The Prionids of the World

Product on sale

€ 39.00

The Prionids of the World

Product on sale

€ 39.00

-

The Prionids of the Neotropical region

Product on sale

€ 59.00

The Prionids of the Neotropical region

Product on sale

€ 59.00

-

The Prionids Collection BundleProduct on sale€ 59.00

The Prionids Collection BundleProduct on sale€ 59.00 -

The Prionids of the WorldProduct on sale€ 39.00

The Prionids of the WorldProduct on sale€ 39.00 -

The Prionids of the Neotropical regionProduct on sale€ 59.00

The Prionids of the Neotropical regionProduct on sale€ 59.00

Books about Beetles

Unique pictorial atlases for identifying Beetles:

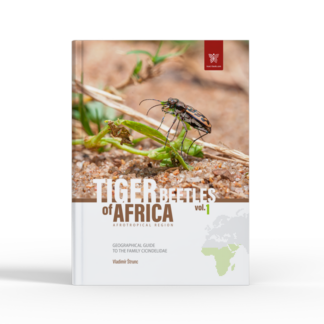

(2020) Tiger Beetles of the World, Cicindelidae, Illustrated guide to the genera

(2023) Tiger Beetles of Africa, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2024) Tiger Beetles of Orient, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2022) Ground Beetles of Africa, Afrotropical Region

(2022) Jewel Beetles of the World, Buprestidae, Illustrated guide to the Superfamily Buprestoidea

(2008) The Prionids of the World, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

(2010) The Prionids of the Neotropical region, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

Taxonomic Diversity and Major Subfamilies

The family Cerambycidae is divided into numerous subfamilies, with classification schemes varying among authorities. Traditionally recognized major subfamilies include:

- Parandrinae: Primitive longhorns with short antennae and mandible-like appearance, often resembling stag beetles. Small subfamily with worldwide distribution.

- Prioninae: Large-bodied beetles, often called sawyers or timber beetles. Includes some of the largest cerambycids. Larvae develop in dead wood of various tree species.

- Spondylidinae: Small subfamily of mostly temperate species associated with conifers. Adults often short-lived with reduced mouthparts.

- Lepturinae: Flower longhorns, often brightly colored and active on flowers during daytime. Large subfamily with greatest diversity in temperate regions.

- Necydalinae: Small subfamily with reduced elytra in some genera, creating wasp-like appearance.

- Cerambycinae: Very large subfamily with diverse morphology and ecology. Includes many familiar species and important pest species.

- Lamiinae: The largest subfamily, extremely diverse in morphology and ecology. Many species have robust bodies and distinctive patterns or tubercles.

Additional smaller subfamilies are recognized by some authorities. Well-known genera include Monochamus, Anoplophora, Rosalia, Cerambyx, Prionus, and Tetraopes, among thousands of others.

How to Identify Cerambycidae

Identifying beetles to family Cerambycidae is generally achievable using distinctive morphological features, though the family’s vast diversity creates challenges and some species may be confused with related families. Species-level identification often requires detailed examination of morphological characters, including tarsal structure, antennal segmentation, and in many cases, male genital structures.

Family-Level Diagnostic Features

Cerambycidae can be recognized by the following combination of characters: elongate antennae typically at least half body length and often much longer, arising from emarginations in the compound eyes or from prominent tubercles; compound eyes typically kidney-shaped or notched where antennae arise; tarsal formula appearing 4-4-4 (actually 5-5-5 with the fourth segment being small and hidden in the bilobed third segment, creating a cryptopentamerous condition); pronotum typically narrower than elytra, often with lateral margins bearing spines or tubercles; elytra usually parallel-sided or tapering posteriorly, covering most of the abdomen.

The antennae are usually filiform (thread-like), serrate (saw-toothed), or pectinate (comb-like) in structure, composed of 11 segments in most species. In males of many species, antennae are longer than in females, sometimes dramatically so. The antennal insertions creating notches or emarginations in the eyes are characteristic and distinguish cerambycids from most other beetle families.

The eyes themselves are typically large and kidney-shaped, wrapped partially around the antennal bases. This configuration provides good visual capability important for finding mates, host plants, and oviposition sites. Eye size and shape vary among subfamilies and relate to activity patterns and ecology.

Subfamily Recognition

While species identification is challenging, many cerambycids can be assigned to subfamily based on external morphology:

Parandrinae: Short antennae barely reaching beyond head; robust, parallel-sided bodies; large mandibles. Superficially resemble stag beetles.

Prioninae: Large size; robust build; antennae serrate or simple, not extremely elongate; lateral margins of pronotum usually with teeth or spines. Often brown or black with relatively simple coloration.

Lepturinae: Often colorful with metallic sheens or warning coloration; elytra frequently tapering posteriorly; many species active on flowers during daytime. Generally smaller than Prioninae.

Cerambycinae: Highly variable; many species elongate and cylindrical; face typically vertical or inclined backward; many tropical species with elaborate patterns or metallic colors.

Lamiinae: Very diverse; face vertical; antennae typically long and gracefully curved; many species with shortened elytra exposing pygidium; often with tubercles, spines, or complex body sculpturing. This subfamily includes enormous morphological diversity.

Sexual Dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism varies considerably among cerambycid species. Common differences include:

- Antennal length: Males often have longer antennae than females, sometimes dramatically so. In some species, male antennae may be several times body length while female antennae are merely slightly longer than body.

- Body size: In many species, females are larger and more robust than males, particularly in the abdomen where egg production requires space. However, this pattern is not universal.

- Mandible size: Some species show sexual dimorphism in mandible development, with males having larger mandibles.

- Tarsal width: Males of many species have broader tarsi, particularly on the front legs, apparently to aid in gripping females during mating.

Coloration and Mimicry

Cerambycid coloration is remarkably diverse. Many species are cryptically colored in browns, grays, or black, often with patterns that camouflage them against bark. Others are brightly colored, exhibiting metallic greens, blues, or reds. Some species have striking patterns including spots, bands, or complex designs.

Aposematic (warning) coloration occurs in species that are toxic or distasteful, often featuring yellow, orange, or red combined with black. Mimicry is well-developed in some groups, with certain cerambycids resembling wasps, bees, or other defended insects. The reduced elytra and wasp-like appearance of some Necydalinae exemplify Batesian mimicry of hymenopterans.

Size Ranges and Variation

The family includes an extraordinary size range. The smallest species measure only 2-3 mm in total length, while the largest exceed 170 mm. Medium-sized species of 10-30 mm are most common. Size variation reflects diverse life histories, with smaller species often developing in small branches or herbaceous stems while larger species require large-diameter logs or trunks for larval development.

Larval Identification

Cerambycid larvae are distinctive and easily recognized by experienced entomologists. The typical larval morphology includes: elongate, cylindrical, somewhat flattened body; reduced or absent legs (most species are legless or have minute vestiges); well-sclerotized head capsule with powerful mandibles; anterior thoracic segments often swollen, creating a distinctive “round-headed” appearance that gives rise to one common name for the family; body segments often with ampullae (swellings) or calluses that aid movement within tunnels.

Larvae create characteristic tunnels in wood, often packed with frass (sawdust-like excrement). Tunnel patterns, frass characteristics, and emergence holes can help identify cerambycid activity even when larvae are not directly observed.

Occurrence and Main Habitats

Longhorn beetles exhibit a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring in virtually all terrestrial ecosystems that support woody plants. Their occurrence patterns reflect both the diversity of woody plant hosts and the varied ecological niches occupied by different species within this enormous family.

Global Distribution Patterns

Cerambycidae occurs on all continents except Antarctica and is well-represented on most oceanic islands with woody vegetation. The family shows its greatest diversity in tropical regions, particularly tropical rainforests, though temperate zones also support rich assemblages. Diversity patterns reflect both current environmental conditions and historical biogeography.

Tropical Regions: Peak diversity occurs in tropical forests, where the combination of high tree diversity, structural complexity, and stable climate supports extraordinary cerambycid richness. Amazonian rainforests, Southeast Asian tropical forests, and Afrotropical forests all harbor thousands of species, many still undescribed.

Temperate Zones: North America, Europe, and temperate Asia support diverse cerambycid faunas, though species richness is lower than in tropical regions. Temperate species often show adaptations to seasonal climates including synchronized emergence and cold-hardy developmental stages.

Mediterranean and Arid Regions: Even relatively dry regions with woody vegetation support adapted cerambycid species, including specialists on desert or drought-adapted plants.

Montane Regions: Mountain forests support distinctive cerambycid assemblages, with species composition changing along elevational gradients. Some species are restricted to high-elevation forests.

Habitat Associations

While specific habitat preferences vary enormously among the thousands of cerambycid species, general patterns can be recognized:

Forest Habitats: The vast majority of cerambycid species are associated with forests, including tropical rainforests, temperate deciduous and coniferous forests, boreal forests, and various woodland types. Forest structure, tree species composition, and dead wood availability all influence cerambycid diversity and abundance.

Woodland and Savanna: Open woodlands, wooded grasslands, and savanna ecosystems support adapted species, often including specialists on fire-adapted or drought-tolerant trees and shrubs.

Riparian Zones: Areas along watercourses often support high cerambycid diversity due to dense woody vegetation, diverse tree species, and favorable microclimate conditions.

Managed Landscapes: Parks, orchards, plantations, and urban areas with trees support cerambycid populations, though diversity is typically lower than in natural forests. Some species thrive in human-modified environments, sometimes becoming pests.

Grasslands and Prairies: Even treeless grasslands may support cerambycid species that develop in woody roots of herbaceous plants or in stems of large forbs.

Host Plant Specificity

Cerambycid species vary considerably in host plant specificity. This variation is fundamental to understanding their ecology, distribution, and diversity:

- Extreme specialists: Some species are monophagous, developing only in a single plant species or genus. This specialization may reflect biochemical adaptation to specific plant chemistry or tight ecological association.

- Moderate specialists: Many species are oligophagous, utilizing several related plant species within a family or group of related families. This represents a common pattern balancing specialization with flexibility.

- Generalists: Some cerambycids are polyphagous, able to develop in diverse, unrelated host plants. Generalists often include pest species capable of attacking various trees or timber.

Host plant associations often correlate with plant chemistry, wood characteristics, and phylogenetic relationships. Conifers, hardwoods, and various other plant groups support distinct cerambycid assemblages, though many species specialize on particular plant families or genera within these broad categories.

Dead Wood Versus Living Plants

An important ecological distinction exists between cerambycids that develop in dead or dying wood versus those that attack living, healthy plants:

Saproxylic species: Many cerambycids develop exclusively in dead, dying, or severely stressed trees. These species play beneficial roles as decomposers, accelerating wood breakdown and nutrient cycling. They require natural tree mortality or disturbance to create suitable breeding substrates.

Primary pests: Other species attack living, healthy trees, acting as primary pests. These beetles must overcome plant defenses including resin production, wound responses, and chemical deterrents. Some species vector fungal pathogens that help overwhelm tree defenses.

Secondary invaders: Intermediate categories include species that attack stressed, damaged, or weakened trees but cannot successfully colonize healthy, vigorous individuals. These secondary borers often follow primary pests or exploit trees weakened by drought, disease, or mechanical damage.

Lifestyle and Behavior

The lifestyle of longhorn beetles encompasses distinct larval and adult phases with fundamentally different behaviors, ecological roles, and habitat use. Understanding cerambycid behavior requires examination of both life stages and the transitions between them.

Adult Activity Patterns and Phenology

Adult cerambycids exhibit diverse activity patterns reflecting phylogenetic heritage, ecological niche, and environmental conditions. Many species are nocturnal, emerging at dusk to engage in feeding, mate-seeking, and oviposition. Nocturnal activity reduces exposure to visual predators and coincides with optimal conditions in many habitats. These species are often attracted to lights, facilitating surveys and collection.

Other species, particularly in subfamily Lepturinae, are diurnal and active on flowers during daylight hours. These flower longhorns are often brightly colored and may function as pollinators while feeding on pollen and nectar. The diurnal activity pattern of flower longhorns differs markedly from the typical nocturnal habits of most cerambycids.

Crepuscular species are active during dawn and dusk periods. In temperate regions, adult emergence is typically synchronized with warm seasons, with peak activity during late spring through summer. In tropical regions with less pronounced seasonality, emergence may be less synchronized, though rainfall patterns often influence phenology.

Adult Feeding Behavior

Adult feeding varies considerably among species. Common food sources include:

- Flowers: Pollen and nectar are important food sources for many species, particularly in Lepturinae. Flower-visiting behavior may contribute to pollination, though most cerambycids are incidental rather than specialized pollinators.

- Bark and cambium: Many species feed on bark, scraping away outer tissues to reach nutritious cambium and phloem. This feeding creates characteristic marks on branches and trunks.

- Leaves and foliage: Some species feed on leaves, creating holes or consuming leaf edges.

- Sap and plant exudates: Tree wounds, sap flows, and fermenting materials attract some species.

- Fungal tissue: Species associated with fungus-infected wood may feed on fungal mycelia.

- Minimal or no feeding: Adults of some species have reduced mouthparts and apparently do not feed, relying on resources accumulated during larval development.

Mate Location and Reproductive Behavior

Mate location in cerambycids involves multiple sensory modalities. Pheromone communication is important in many species, with females producing volatile chemicals that attract males over considerable distances. Male antennae, often more elaborate than those of females, may be specialized for detecting female pheromones. Visual cues also play roles, with adults locating potential mates on host plants or at aggregation sites.

Courtship behavior varies from minimal interaction to elaborate sequences. In many species, males locate females on or near host plants, approach, and mate with little apparent courtship. Other species exhibit antennal tapping, stroking, or other contact behaviors before mating. Males may guard females after copulation to prevent rival matings, particularly in species where males can monopolize individual females or host plant resources.

Mating typically occurs on or near host plants, though some species mate on flowers or other substrates. Copulation duration varies from minutes to hours depending on species.

Oviposition Behavior

Females locate suitable oviposition sites using visual and chemical cues. Host plant volatile emissions, particularly from wounded or stressed plants, may attract gravid females. Once a suitable host is located, females assess its quality, apparently discriminating among potential sites based on factors including bark texture, wood condition, presence of fungi, and possibly chemical composition.

Oviposition behavior varies among subfamilies and species. Common patterns include:

Bark oviposition: Females chew small pits or crevices in bark and deposit eggs individually. Bark thickness, texture, and condition influence site selection. Some species prefer smooth bark, others select rough or damaged areas.

Wood crevice oviposition: Eggs are deposited in bark crevices, under bark scales, or in existing cracks in wood. This protects eggs and positions hatching larvae near suitable wood.

Direct wood insertion: Some species use elongate ovipositors to insert eggs directly into wood through bark, placing eggs in optimal positions for larval development.

Females may deposit from dozens to hundreds of eggs depending on species and conditions. Eggs are usually distributed across multiple host individuals or sites, reducing risk associated with any single site failing.

Adult Dispersal and Flight

Most adult cerambycids are capable fliers, with flight important for dispersal, mate location, and host finding. Flight capability varies among species, with some being strong, sustained fliers while others are weak fliers that travel only short distances. Flight activity often peaks during particular daily periods, frequently at dusk or during evening hours.

Dispersal distances vary considerably. Mark-recapture studies of various species have documented movements ranging from tens of meters to several kilometers. Long-distance dispersal allows colonization of new habitats and maintains gene flow among populations, but also facilitates spread of pest species into new regions.

Larval Behavior and Wood-Boring

Larval behavior is dominated by feeding and tunnel excavation. After hatching, the first instar larva typically feeds in or just beneath bark, creating small galleries. As larvae grow through successive molts, they bore deeper into wood, creating increasingly large tunnels. The round-headed appearance of cerambycid larvae, with enlarged anterior thoracic segments, facilitates movement within tight tunnels.

Tunneling patterns are species-specific and reflect both larval morphology and wood characteristics. Tunnels may run parallel to grain, across grain, or in complex patterns. Frass is typically pushed behind the advancing larva, packing tunnels. Some species create exit holes to eject frass, while others pack it tightly in galleries.

Larval development duration varies tremendously, from several months in fast-developing species to several years in species requiring extensive feeding periods. Large species developing in hard wood may require three to five years or more to complete development. Temperature, wood quality, moisture, and fungal associations all influence development rates.

Defensive Behaviors

Adult cerambycids employ various defensive strategies when threatened. The hardened exoskeleton provides primary protection. Many species produce sounds through stridulation (rubbing body parts together), creating squeaking or hissing noises that may startle predators. Stridulatory organs vary in location but often involve rubbing the pronotum against mesothoracic structures.

Chemical defenses occur in some species. Certain taxa produce toxic or deterrent compounds that make them unpalatable to predators. Aposematic coloration in some species advertises chemical defenses. Reflex bleeding (releasing hemolymph) occurs in some species when handled.

Escape responses include flight (when possible), dropping from perches and remaining motionless, or rapid running. Some species wedge themselves into crevices making extraction difficult. Larvae, being concealed within wood, rely primarily on their protected location for defense, though some produce sounds that may deter predators.

Food and Role in the Ecosystem

Longhorn beetles play multifaceted ecological roles as herbivores, decomposers, and prey organisms. Their impacts on ecosystems vary from beneficial decomposition to economically significant pest damage, with most species falling somewhere between these extremes as ecologically integrated components of forest communities.

Larval Feeding Ecology and Wood Consumption

The vast majority of cerambycid larvae are xylophagous (wood-feeding), consuming woody tissues of trees, shrubs, vines, or occasionally herbaceous plants with woody stems. This fundamental feeding mode defines the family’s ecology and distinguishes cerambycids from most other beetle families.

Wood is a nutritionally challenging substrate, consisting primarily of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin with relatively low nitrogen content and few readily available nutrients. Cerambycid larvae have evolved multiple adaptations for extracting nutrition from this recalcitrant resource:

Mechanical processing: Powerful mandibles chew wood into fine particles, increasing surface area for enzymatic attack and passage through the gut. The physical breakdown of wood structure is itself an important contribution to decomposition.

Endogenous enzymes: Cerambycid larvae produce various digestive enzymes that break down components of plant cell walls. The extent of endogenous cellulase production varies among species.

Microbial symbionts: The larval gut harbors complex communities of bacteria, yeasts, and fungi that produce cellulases, hemicellulases, and other enzymes essential for wood digestion. These microorganisms are crucial for extracting nutrients from wood. The diversity and composition of gut microbial communities vary among cerambycid species and may influence host plant range and wood preferences.

Fungal associations: Many cerambycids are associated with wood-decay fungi. Fungal colonization pre-digests wood, breaking down lignin and other compounds while enriching nutritional content. Some species appear to require or strongly prefer fungally colonized wood. The relationships between cerambycids and fungi range from casual association to apparent obligate dependence, though the specifics remain poorly understood for most species.

Feeding patterns vary among species and subfamilies. Some larvae feed primarily in cambium and phloem (the nutrient-rich tissues just beneath bark), creating meandering galleries that may girdle branches or stems. Others bore into sapwood (the outer, living wood) or heartwood (the inner, dead wood). Different feeding niches reflect adaptations to different wood characteristics and nutritional strategies.

Adult Feeding and Resource Use

Adult feeding ecology varies considerably as described previously. The importance of adult feeding for reproduction differs among species. In some taxa, adults feed extensively and adult nutrition is crucial for egg production and longevity. In others, adults feed minimally or not at all, relying primarily on resources accumulated during larval development. Species with short adult lifespans often show reduced feeding, while longer-lived adults typically feed more extensively.

Ecosystem Roles and Services

Dead Wood Decomposition: Saproxylic cerambycids play crucial roles in decomposing dead and dying woody material. Their larvae fragment wood, accelerate physical breakdown, and create conditions facilitating further fungal and bacterial decomposition. By consuming wood and converting it to frass and insect biomass, they contribute substantially to nutrient cycling and energy flow in forest ecosystems.

Nutrient Cycling: Cerambycid feeding transforms woody biomass, releasing nutrients sequestered in recalcitrant plant tissues. Nitrogen and other nutrients become available to other organisms through beetle excretion, death, and decomposition. In forests with high cerambycid populations, their contribution to nutrient cycling is substantial.

Habitat Creation: Larval tunnels and emergence holes create microhabitats utilized by numerous other organisms. Cavity-nesting bees, wasps, and other insects use abandoned cerambycid tunnels for nesting. Fungi, bacteria, and mites colonize tunnels. Some vertebrates use large emergence holes as access points to excavate larger cavities.

Food Web Dynamics: Cerambycids serve as prey for diverse predators throughout their life cycle. Larvae are consumed by woodpeckers and other birds that excavate them from wood, by wood-boring predaceous beetle larvae, by parasitoid wasps and flies, and by various other predators. Adults are eaten by birds, bats, reptiles, amphibians, spiders, and predaceous insects. The substantial biomass represented by cerambycid populations contributes significantly to energy transfer in food webs.

Pollination Services: Some flower-visiting cerambycids, particularly in Lepturinae, may contribute to pollination while feeding on pollen and nectar. While most are probably inefficient pollinators compared to specialized pollinators like bees, their visitation to flowers may provide some pollination service, particularly in ecosystems where other pollinators are scarce.

Indicators of Forest Health: Because many cerambycids are specialists requiring particular tree species, wood conditions, or forest characteristics, they can serve as indicators of forest ecosystem health and integrity. Diverse cerambycid assemblages indicate diverse tree communities and natural forest dynamics including tree mortality and dead wood accumulation.

Pest Species and Economic Impacts

Forest and Timber Pests: While most cerambycids are ecologically beneficial or neutral, some species cause significant economic damage as forest or timber pests. These species attack living trees, reduce timber value through tunneling damage, or vector fungal pathogens. Important pest genera include:

- Anoplophora – Asian longhorned beetles that attack numerous hardwood species, causing severe damage in invaded regions

- Monochamus – Pine sawyers that vector pine wilt nematode, a devastating pathogen of conifers

- Tetropium – Roundheaded woodborers attacking conifers

- Saperda – Roundheaded borers attacking various hardwoods including fruit trees

Some pest species are native organisms that occasionally reach outbreak densities, while others are invasive species introduced outside their native ranges where they lack natural enemies and can cause severe damage. Invasive cerambycids represent serious threats to forest ecosystems and urban tree resources.

Vector Relationships: Some cerambycids transmit fungal or nematode pathogens that cause tree diseases. The pine wilt disease complex, involving Monochamus beetles and pinewood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus), exemplifies these vector relationships. Adult beetles acquire nematodes during emergence from infected trees and transmit them to healthy trees during feeding, spreading disease across landscapes.

Life Cycle

Longhorn beetles undergo complete metamorphosis (holometaboly) with four distinct life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The life cycle is characterized by an often prolonged larval period of wood-feeding followed by pupal transformation and typically brief adult life focused on reproduction and dispersal.

Egg Stage

After mating, females locate suitable host plants and oviposition sites. The process of host selection involves assessment of plant species identity, physiological condition, and specific microsite characteristics. Females use visual cues, olfactory signals, and possibly tactile evaluation of bark texture and chemistry to discriminate among potential hosts.

Eggs are typically deposited individually, though some species may place several eggs in close proximity. Oviposition involves chewing a small pit, crevice, or slit in bark where the egg is deposited. Some species have elongate ovipositors allowing egg placement beneath bark or within wood. Eggs are usually oval, whitish to cream colored, and relatively small (typically 1-4 mm in length depending on species size).

Egg development duration depends on temperature and species but typically ranges from one to three weeks. Warmer temperatures accelerate development while cooler conditions extend the egg period. Upon hatching, the neonate larva typically remains near the egg site initially, feeding in bark or just beneath it before boring more deeply into wood.

Larval Stage and Development

The larval stage represents the growth and feeding period, constituting the majority of the cerambycid life cycle. Larvae are legless or nearly so (some species have minute vestiges of thoracic legs), elongate, cylindrical, and somewhat dorso-ventrally flattened. The head is well-sclerotized with powerful mandibles adapted for chewing wood. The prothorax is typically enlarged, creating the characteristic “round-headed” profile.

Body coloration is usually cream to white, though the gut contents (visible through the translucent cuticle) may impart yellowish or brownish tones. The body surface may be smooth or bear various setae, spines, or tubercles that aid movement within tunnels. Abdominal segments often have paired ampullae (swellings) that function in locomotion through tunnels.

Larval development proceeds through multiple instars, typically ranging from 3 to 10 or more depending on species, with each instar separated by a molt. The exact number of instars can vary within species depending on food quality, temperature, and other environmental factors. Head capsule width increases with each molt and provides a means of determining instar.

Growth is continuous within instars, with larvae accumulating biomass through constant feeding. Larval development duration varies tremendously among species and environmental conditions, from as little as several months in small, fast-developing species to five years or more in large species developing in hard wood or cool climates. Tropical species in warm, stable environments may develop more rapidly than temperate species experiencing seasonal temperature fluctuations.

The feeding patterns and tunnel construction create characteristic signs of cerambycid activity. Tunnel diameter increases as larvae grow, and tunnels often become packed with frass behind the advancing larva. Some species create periodic exit holes to expel frass, while others push it into side galleries or pack it tightly in used portions of tunnels.

As the final larval instar approaches completion of feeding, the larva typically excavates a pupal chamber. This chamber is often located near the wood surface to facilitate adult emergence but protected by a layer of wood or bark. The chamber may be oriented perpendicular to the grain with the pupal head toward the surface, allowing the emerging adult to bore directly outward.

Pupal Stage

Pupation occurs within the chamber after the final larval molt produces the pupa. The pupa is exarate (with free appendages), clearly showing developing adult structures including legs, antennae, wings, and body form. In species with elongate antennae, the pupal antennae are folded back along the body or curled in the chamber.

Initially pale and soft, the pupa gradually sclerotizes and develops adult coloration during the pupal period. The developing adult structures within the pupal cuticle become increasingly apparent as development progresses. In species with bright colors or patterns, pigmentation develops during the later pupal stages.

Pupal duration varies with temperature and species but typically ranges from two to four weeks in most species. The pupa is immobile and vulnerable, relying entirely on the protective chamber for survival. Temperature extremes, flooding, or predator penetration of the chamber can cause mortality.

Adult Emergence and Teneral Period

The fully formed adult emerges from the pupal cuticle (eclosion) within the pupal chamber. The newly emerged adult (teneral adult) is initially soft and pale with incompletely hardened cuticle and undeveloped coloration. Over a period of days to weeks, the exoskeleton sclerotizes and develops its final hardness and coloration. The elytra, initially soft and flexible, harden and develop their characteristic texture and color pattern.

During the teneral period, the adult remains within or very near the pupal chamber, allowing cuticle hardening in a protected environment. In many temperate species, adults complete development in late summer or autumn but remain within the pupal chamber over winter, emerging the following spring when conditions favor reproduction. This extended teneral period, which may last many months, is called adult diapause.

Emergence from wood occurs when environmental cues indicate appropriate conditions. The adult chews an exit tunnel to the wood surface, creating the characteristic emergence hole. Emergence hole shape (typically round in cerambycids, distinguishing them from oval holes of some other wood borers) and size provide clues to species identity. Upon reaching the surface, the fully hardened adult begins normal activities including dispersal, feeding, and reproduction.

Adult Longevity and Reproduction

Adult lifespan varies considerably among species and environmental conditions. Many cerambycids live only several weeks as adults, with reproduction occurring during this brief period. Adults with extensive feeding requirements or those emerging early relative to optimal mating times may live several months.

Some flower-visiting species that feed extensively on pollen and nectar can survive several months under favorable conditions. Conversely, species with reduced mouthparts and minimal feeding may live only days to weeks, just long enough to mate and oviposit.

Reproductive output varies but females typically produce dozens to hundreds of eggs over their lifetime, distributed across multiple host plants or sites. In species where adults feed extensively, reproductive output may be correlated with feeding success and adult longevity.

Voltinism and Phenology

The number of generations per year (voltinism) varies among cerambycid species. Most are semivoltine (requiring more than one year to complete development) or have generation times of one to several years. The prolonged larval development period characteristic of most wood-boring cerambycids results in these extended life cycles.

Small species developing in thin branches, herbaceous stems, or under bark may complete development within a single growing season, producing one generation per year (univoltine). These fast-developing species typically have shorter adult life spans and more synchronized emergence.

Large species developing in hard wood or in cool climates may require two, three, or even five or more years to complete development. In these species, adult emergence is less synchronized, with individuals from multiple cohorts potentially emerging in the same season. Understanding generation times is important for predicting population dynamics and managing pest species.

In temperate regions, adult emergence is typically synchronized with warm seasons, creating distinct flight periods during late spring through summer. Some species have early season emergence while others peak in mid or late summer. In tropical regions with less pronounced seasonality, emergence may be less tightly synchronized, though rainfall patterns often influence phenology.

Bionomics – Mode of Life

The bionomics of longhorn beetles encompasses their interactions with physical environments, host plants, other organisms, and ecosystem processes. Understanding how these beetles function within ecological contexts provides comprehensive insight into their evolution, diversity, and importance.

Host Plant Relationships and Coevolution

The relationship between cerambycids and their host plants represents a fundamental axis of their biology. Host plant associations range from extreme specialization to broad generalization, with most species falling somewhere intermediate. These associations reflect evolutionary history, biochemical constraints, and ecological opportunity.

Plant defenses against herbivores include physical barriers (bark thickness and texture, wood hardness, resin canals), chemical deterrents (toxic secondary compounds, digestibility reducers), and induced responses (increased resin flow, callus formation, defensive compound production). Cerambycids must overcome these defenses to successfully colonize hosts, leading to coevolutionary dynamics between beetles and plants.

Specialist cerambycids have evolved detoxification systems, behavioral adaptations, or symbiotic relationships allowing them to exploit particular host groups. This specialization can constrain host range but may provide competitive advantages by allowing use of resources inaccessible to generalists. Specialists often have intimate knowledge (evolved through natural selection) of host phenology, microsite characteristics, and optimal colonization timing.

Generalist species must maintain flexibility in detoxification systems and accept lower efficiency in utilizing any single host in exchange for the ability to exploit diverse resources. Generalization may be advantageous in disturbed or changing environments where preferred hosts are unpredictable.

Wood Characteristics and Substrate Preferences

Wood is a heterogeneous resource varying in moisture content, hardness, chemistry, decay stage, diameter, and position. These characteristics profoundly influence cerambycid colonization and development success.

Moisture: Wood moisture content affects larval survival, development rate, and wood suitability. Most cerambycids require moist wood, with desiccation causing mortality. However, wood that is waterlogged or excessively wet may be unsuitable. Moisture requirements vary among species, with some preferring relatively dry dead wood while others require fresh, moist material.

Wood hardness and decay stage: Wood hardness influences which cerambycid species can successfully colonize. Soft-wooded trees are accessible to more species than hard-wooded trees requiring powerful mandibles and extended development periods. Wood decay stage is critical, with some species requiring fresh dead wood, others preferring intermediate decay stages, and some specializing on highly decayed, friable wood.

Diameter and position: Wood diameter affects microclimate stability, available volume for larval development, and resource persistence. Large-diameter logs provide more stable thermal and moisture conditions than small branches. Wood position (standing dead trees, fallen logs, stumps, buried roots) influences exposure, moisture, and fungal colonization patterns.

Fungal Associations and Symbioses

Relationships between cerambycids and fungi are complex and varied. Wood-decay fungi modify wood chemistry and structure, often making it more suitable for beetle colonization. The nature of these relationships ranges from passive association to apparent obligate dependence.

Some cerambycids apparently require fungally colonized wood, with larvae developing poorly or failing to develop in wood lacking appropriate fungi. Whether beetles actively inoculate wood with fungi or simply exploit colonized material varies among species. Some cerambycids may vector fungal spores, establishing symbiotic relationships where beetles disperse fungi that pre-digest wood for larval consumption.

The gut microbiome includes fungal components that may contribute to wood digestion. Whether these are true symbionts, environmental acquisitions, or dietary items remains unclear for most species. Understanding cerambycid-fungal relationships is an active research area with implications for both basic biology and applied pest management.

Natural Enemies and Mortality Factors

Cerambycids face mortality from diverse sources throughout their life cycle, influencing population dynamics and evolution of defensive adaptations.

Predators: Larvae within wood are consumed by woodpeckers and other birds that excavate them, by predaceous beetle larvae (particularly in families Cleridae, Trogositidae, and some Cerambycidae), and by various other predators. Adults are preyed upon by birds, bats, spiders, assassin bugs, robber flies, and numerous other predators. Eggs may be eaten by various small predators including ants and mites.

Parasitoids: Numerous parasitoid wasps and flies attack cerambycid larvae, with different parasitoid species specializing on different host beetle taxa or life stages. Parasitoid wasps may have elongate ovipositors allowing them to reach deep-boring larvae. Some parasitoids locate hosts by detecting larval feeding sounds or vibrations. Parasitism rates vary tremendously but can be substantial in some populations.

Pathogens: Fungal, bacterial, and viral diseases cause mortality in both larvae and adults. Entomopathogenic fungi can infect larvae in wood, particularly in moist conditions. Bacterial and viral infections may spread through populations, occasionally causing epizootics that reduce densities.

Competition: Intraspecific and interspecific competition for limited host resources influences survival and development. High larval densities in preferred hosts can lead to resource depletion, reduced growth rates, increased development time, and smaller final adult size. Competition with other wood-boring insects including beetles, moths, and flies occurs where species overlap in resource use.

Temperature and Climate Constraints

As ectothermic organisms, cerambycids are fundamentally influenced by temperature. Development rates, adult activity, and survival are temperature-dependent within species-specific thermal tolerance ranges. Larvae developing within wood experience buffered thermal conditions compared to exposed environments, with large-diameter logs providing particularly stable temperatures.

Seasonal temperature patterns in temperate regions result in synchronized phenology, with development timed to allow adult emergence during favorable periods. Cold winter temperatures are survived through physiological cold hardiness in larvae or diapausing adults. Tropical species experience less thermal variation but may be synchronized with rainfall patterns.

Climate change is shifting thermal regimes, potentially affecting cerambycid distributions, voltinism, and synchronization with host plants. Warming may allow range expansions, increase development rates, or disrupt evolved thermal cues. Understanding thermal biology is increasingly important for predicting responses to changing climates.

Dispersal and Metapopulation Dynamics

Cerambycid populations are often distributed as metapopulations, with local breeding sites connected by adult dispersal. Suitable habitat occurs as patches (dead wood resources, stands of host trees) separated by unsuitable matrix. Adults disperse among patches, allowing colonization of new resources and gene flow among populations.

Dispersal capability varies among species and influences metapopulation dynamics. Strong fliers can traverse larger distances, maintaining connectivity across fragmented landscapes. Weak fliers may have limited dispersal ranges, making populations more isolated and vulnerable to local extinction. Habitat connectivity, patch size and quality, and dispersal distance interact to determine metapopulation persistence.

Distribution

The distribution of family Cerambycidae reflects the interplay of evolutionary history, host plant distributions, climatic constraints, and dispersal capabilities. Understanding distribution patterns requires consideration of scales from global to local and recognition of factors limiting occurrence.

Global Biogeography and Diversity Patterns

Cerambycidae exhibits a cosmopolitan distribution with representation in all major biogeographic regions and occurrence from arctic tree lines to tropical rainforests. The family’s worldwide distribution reflects ancient origins and broad ecological tolerances, though diversity is not evenly distributed globally.

Tropical regions harbor the highest diversity, with peak richness in tropical rainforests of South America, Southeast Asia, and Central Africa. The Amazon basin, Bornean rainforests, and Congo basin all support thousands of cerambycid species, many undescribed. This tropical diversity center reflects multiple factors including high host plant diversity, stable warm climates permitting year-round activity, complex forest structure creating diverse niches, and long evolutionary history without major climatic disruptions.

Temperate regions support substantial diversity, though species richness is lower than in tropics. Diverse assemblages occur in temperate forests of North America, Europe, East Asia, and temperate South America. Some temperate regions, particularly East Asia, harbor exceptional diversity reflecting both current favorable conditions and historical factors including glacial refugia.

Mediterranean and other warm temperate regions support distinctive faunas adapted to seasonal drought and fire-prone environments. Boreal forests at high latitudes support lower diversity but include specialized species adapted to cold climates and coniferous hosts.

Host Plant Distributions and Cerambycid Ranges

Because most cerambycids are associated with particular host plants or plant groups, their distributions are fundamentally linked to host distributions. Specialist species have ranges constrained by host plant ranges, while generalists may have broader distributions reflecting their ability to utilize diverse hosts.

Specialist-host relationships create interesting biogeographic patterns. Cerambycids specialized on particular tree genera or families have ranges overlapping host distributions, with range limits often corresponding to host range boundaries. Disjunct host distributions may result in disjunct cerambycid ranges, with isolated populations in separated portions of host ranges.

Host plant phylogeny influences cerambycid distributions and diversity. Plant families with high diversity and wide distributions tend to support rich associated cerambycid faunas. Conversely, plant groups with limited distributions have restricted associated cerambycid assemblages.

Regional Endemism and Refugia

Many cerambycid species exhibit restricted distributions, with endemism occurring at various scales from single mountains or islands to broader regions. Island faunas are particularly notable for endemism, with oceanic islands supporting unique species that evolved in isolation.

Historical climate changes, particularly Pleistocene glacial-interglacial cycles, have shaped current distributions. Glacial refugia where forests persisted during cold periods served as centers from which species recolonized deglaciated regions. Phylogeographic patterns reflect these historical processes, with genetic structure showing signatures of refugial isolation and post-glacial expansion.

Mountain regions often harbor endemic species adapted to high-elevation conditions. Montane forests may have served as refugia during warm periods, allowing persistence of cold-adapted species that subsequently became isolated on mountain tops as climates warmed.

Elevational Zonation and Gradients

Within regions, cerambycids exhibit elevational zonation reflecting temperature, vegetation, and host plant gradients. Different species occupy different elevational bands, with lowland specialists, montane species, and in some regions subalpine or even alpine species creating turnover along elevational transects.

Elevational limits may reflect physiological thermal constraints, host plant distributions, or biotic interactions including competition and predation. Some species show plasticity in elevational range, occurring broadly across gradients, while others are restricted to narrow elevational bands.

Anthropogenic Range Changes and Invasions

Human activities have substantially altered cerambycid distributions through habitat modification, international trade, and climate change. Deforestation and forest fragmentation have reduced or eliminated populations from formerly occupied areas. Conversely, plantation forestry and ornamental tree planting have created new host resources allowing range expansions for some species.

International trade in wood, wood products, and live plants has facilitated accidental introductions of cerambycids outside their native ranges. Several species have become serious invasive pests, including the Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) in North America and Europe, and various other species spread through global commerce.

These invasive species often lack natural enemies in introduced ranges, allowing population explosion and severe impacts on native forests and urban trees. Understanding dispersal mechanisms and pathway of introduction is crucial for preventing future invasions and managing established invasive populations.

Climate change is influencing distributions through range shifts as thermal zones move poleward and upward in elevation. Some species are expanding at range margins while potentially contracting at warm limits. Monitoring distribution changes and understanding drivers is essential for predicting future patterns and conserving vulnerable species.

Main Scientific Literature Citing

The scientific literature on longhorn beetles is vast, reflecting both the family’s enormous diversity and its economic importance. The following represents key research areas and significant contributions, though comprehensive coverage is impossible given the extensive body of work.

Taxonomic and Systematic Works

Systematic understanding of Cerambycidae has developed through centuries of taxonomic work, from early descriptions by Linnaeus and other pioneering naturalists to contemporary revisions using morphological and molecular methods. Major contributions include comprehensive catalogs documenting global diversity, regional faunal treatments, generic and tribal revisions, and phylogenetic analyses resolving evolutionary relationships.

Monné, M. A. and colleagues have produced important catalogs of New World cerambycids. Löbl, I. and Löding, H. P. have contributed to comprehensive catalogs of Palearctic beetles. Numerous regional specialists have produced faunal treatments for particular geographic areas. These foundational works provide essential taxonomic infrastructure for ecological and applied research.

Phylogenetic studies using morphological and molecular data have clarified relationships within and among subfamilies. Recent phylogenomic analyses using transcriptome or genomic data are resolving long-standing questions about cerambycid evolution and revealing unexpected relationships that revise traditional classifications.

Morphology, Development, and Sexual Selection

Morphological studies have documented the remarkable diversity of cerambycid body forms, antenna structures, and coloration patterns. Research on antennal evolution has examined how these structures function in chemoreception and mate location, and how sexual selection has driven elongation in males of many species.

Developmental studies have investigated the mechanisms underlying antenna development, body size variation, and sexual dimorphism. Understanding how nutrition during larval development influences final adult size and secondary sexual characters provides insights into developmental plasticity and evolution of exaggerated traits.

Chemical Ecology and Pheromone Communication

Chemical ecology research has identified pheromones used in mate location and aggregation by numerous cerambycid species. These studies have revealed the chemical structures of pheromones, behavioral responses to pheromones, and evolution of pheromone systems. Understanding chemical communication has both basic scientific interest and applied implications for pest monitoring and management.

Research on plant volatile emissions and cerambycid host-finding behavior has shown how beetles locate and assess potential hosts. Volatile compounds from stressed or damaged trees attract cerambycids seeking oviposition sites. Some species respond to compounds from specific host groups, while others respond broadly to stress-induced volatiles.

Larval Ecology and Wood Decomposition

Ecological research has investigated larval substrate preferences, development rates in different hosts, and effects of temperature and moisture on survival and development. Studies of wood decomposition processes have quantified cerambycid contributions to nutrient cycling and energy flow in forest ecosystems.

Research on gut microbiomes has characterized bacterial, fungal, and protist communities facilitating wood digestion. These studies have identified key lignocellulolytic organisms and enzymes, providing insights into symbiotic relationships and potential biotechnology applications.

Investigations of cerambycid-fungal relationships have examined whether beetles vector specific fungi, whether fungi are required for successful development, and how fungal colonization affects wood suitability. Understanding these relationships is important for both basic ecology and applied pest management.

Pest Biology and Management

Extensive research has focused on economically important pest species, examining population dynamics, damage assessment, host preferences, dispersal capabilities, and control strategies. Studies of Asian longhorned beetle have investigated detection methods, eradication approaches, and factors influencing establishment success in introduced ranges.

Research on pine wilt disease has examined the complex interactions among Monochamus beetles, pinewood nematode, and host pine trees. Understanding vector biology, nematode transmission, and disease epidemiology informs management strategies for this devastating forest disease.

Development of monitoring techniques using pheromones or plant volatiles has provided tools for detecting infestations, predicting population trends, and targeting management interventions. Biological control research has investigated natural enemies including parasitoids and pathogens that might be utilized against pest species.

Conservation Biology and Saproxylic Beetles

Conservation research has assessed population status of threatened cerambycid species, identified habitat requirements, and developed management recommendations. Studies of rare and endangered species have examined factors limiting distributions and populations, providing guidance for conservation planning.

Research on saproxylic beetle conservation has highlighted the importance of dead wood retention in managed forests, old-growth forest protection, and landscape-scale planning to maintain habitat connectivity. These studies demonstrate that cerambycid diversity depends on continuous availability of suitable dead wood resources across landscapes.

Some spectacular or rare species including Rosalia alpina in Europe have received particular conservation attention, with research documenting habitat requirements, dispersal capabilities, and responses to management interventions. These species serve as flagships for saproxylic insect conservation more broadly.

Invasion Biology and Risk Assessment

Research on invasive cerambycids has examined pathways of introduction, factors influencing establishment success, impacts on invaded ecosystems, and effectiveness of prevention and control measures. Risk assessment models have been developed to predict which species pose greatest invasion threats and which regions are most vulnerable.

Understanding wood packaging material as a pathway for cerambycid introductions has led to international phytosanitary standards requiring heat treatment or fumigation. Research documenting the effectiveness of these treatments continues to inform quarantine protocols.

Climate Change and Phenology

Recent research has investigated how climate change affects cerambycid distributions, voltinism, and phenological synchronization with hosts. Studies using historical collection records, museum specimens, and long-term monitoring data have documented range shifts and phenological changes correlating with warming temperatures.

Experimental studies manipulating temperature have examined thermal tolerance limits, degree-day requirements for development, and potential for voltinism increases under warmer conditions. These studies help predict future responses to continued climate change.

Key Research Themes and Future Directions

Current research priorities and emerging areas include:

- Phylogenomics to resolve relationships and understand diversification patterns in this enormous family

- Functional metagenomics of gut microbiomes to understand wood digestion and identify novel enzymes

- Climate change impacts on distributions, phenology, voltinism, and host-cerambycid synchronization

- Invasion pathway analysis and risk assessment to prevent future introductions

- Conservation genetics of threatened species to guide protection efforts

- Chemical ecology including pheromone identification and semiochemical applications

- Ecosystem services quantification of beneficial decomposer species

- Host plant coevolution and diversification patterns

The extensive scientific literature reflects cerambycids’ importance as diverse, ecologically significant, and economically important beetles. Continued research promises further insights into their biology while contributing to forest ecosystem understanding, pest management, and biodiversity conservation.

Family Cerambycidae: Longhorn Beetles

-

Tiger Beetles of Orient€ 129.00

Tiger Beetles of Orient€ 129.00 -

Tiger Beetles of Africa€ 129.00

Tiger Beetles of Africa€ 129.00 -

The Prionids Collection BundleProduct on sale€ 59.00

The Prionids Collection BundleProduct on sale€ 59.00 -

Ground Beetles of Africa (2nd edition)€ 136.00

Ground Beetles of Africa (2nd edition)€ 136.00 -

Jewel Beetles of the World€ 105.00

Jewel Beetles of the World€ 105.00 -

Tiger Beetles of the World€ 109.00

Tiger Beetles of the World€ 109.00

Conclusion Longhorn beetles

Longhorn beetles represent one of the most diverse, ecologically important, and economically significant beetle families. With tens of thousands of species distributed worldwide, Cerambycidae exemplifies the extraordinary diversity that characterizes the order Coleoptera. The family’s characteristic elongate antennae, wood-boring larval habits, and often spectacular adult morphology and coloration have made these beetles subjects of scientific study, economic concern, and aesthetic appreciation.

The fundamental role of cerambycids as wood-borers defines their ecology and importance in forest ecosystems. As larvae, they consume dead and living woody tissues, contributing substantially to decomposition processes and nutrient cycling. Their tunneling fragments wood, accelerates physical breakdown, and creates microhabitats utilized by numerous other organisms. In natural forests with abundant dead wood, cerambycid contributions to ecosystem function are substantial and beneficial.

However, the same wood-boring habits that make many cerambycids ecologically beneficial can also create economic problems when species attack commercial timber, forest trees, or urban ornamentals. Understanding the biology and ecology of pest species is essential for developing effective, sustainable management strategies that minimize damage while preserving the beneficial roles of non-pest species.

The remarkable diversity of Cerambycidae reflects complex evolutionary radiations driven by host plant specialization, sexual selection on antennal and body size traits, and adaptation to varied environmental conditions. Host plant associations range from extreme specialization to broad generalization, with corresponding effects on distributions, ecological interactions, and conservation status. Sexual selection on male antennal length has driven evolution of spectacularly elongate antennae in many species, creating some of the most visually striking insects.

Conservation challenges facing cerambycids include habitat loss and degradation, particularly removal of dead wood from managed forests that eliminates substrate essential for saproxylic species. Climate change poses emerging threats through altered thermal regimes, phenological mismatches with hosts, and potential range contractions for specialized species. Conversely, some pest species may benefit from warming temperatures, expanding ranges and increasing voltinism.

The accidental introduction of cerambycids outside their native ranges through international trade represents a serious threat to forest ecosystems and urban trees worldwide. Several invasive species have caused severe economic and ecological damage in introduced ranges. Preventing future introductions requires robust quarantine systems, international cooperation, and continued research on invasion pathways and risk factors.

Future research will continue revealing insights into cerambycid biology from molecular mechanisms of development and digestion to ecosystem-level impacts of their activities. The enormous diversity of the family, much of it still poorly documented, represents a vast frontier for taxonomic, ecological, and evolutionary investigation. Understanding these remarkable beetles contributes not only to knowledge of Cerambycidae itself but to broader comprehension of insect diversity, evolution, forest ecology, and the complex interactions between herbivores and plants.

Longhorn beetles will undoubtedly continue to fascinate scientists, pest managers, conservationists, and naturalists while playing their crucial roles in forest ecosystems worldwide. Balancing their beneficial ecosystem services with management of damaging pest species represents an ongoing challenge requiring integration of ecological understanding with practical management approaches.

wikipedia