Unique atlases with photos. Beetles represent the most diverse order of insects on Earth, with approximately 400,000 known species constituting roughly one in every four animals on the planet.

Beetles

Book novelties:

Prioninae of the World I., Cerambycidae of the Western Paleartic I. June Bugs,

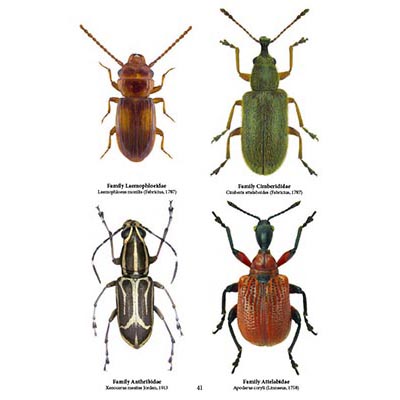

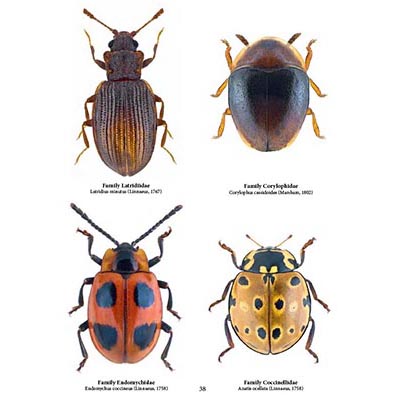

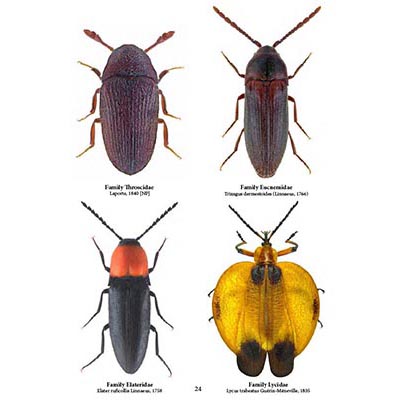

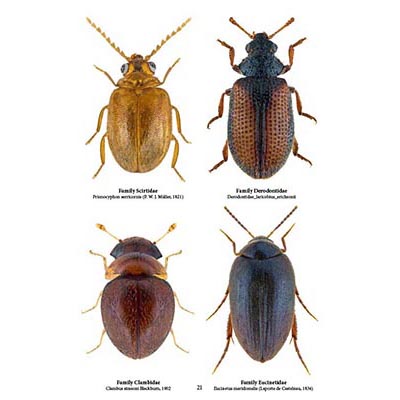

Types of beetles insects

New E-Book: Ground Beetles, Tiger Beetles, Longhorn Beetles, Jewel Beetles, Stag Beetles, Carpet Beetles, Scarab Beetles, Rhinoceros Beetles

Kinds of beetles insects

We recommend:

jeweled beetles, ground beetles, longhorn beetles, goliath beetle, stag beetle, carpet beetles

-

Types of beetles insects€ 13.00

Types of beetles insects€ 13.00 -

Tiger Beetles of Orient€ 129.00

Tiger Beetles of Orient€ 129.00 -

Tiger Beetles of Africa€ 129.00

Tiger Beetles of Africa€ 129.00 -

The Prionids of the WorldProduct on sale€ 39.00

The Prionids of the WorldProduct on sale€ 39.00 -

Ground Beetles of Africa (2nd edition)€ 136.00

Ground Beetles of Africa (2nd edition)€ 136.00 -

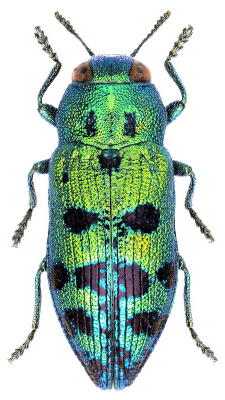

Jewel Beetles of the World€ 105.00

Jewel Beetles of the World€ 105.00 -

Tiger Beetles of the World€ 109.00

Tiger Beetles of the World€ 109.00 -

The Prionids of the Neotropical regionProduct on sale€ 59.00

The Prionids of the Neotropical regionProduct on sale€ 59.00

The Remarkable Diversity of Beetles

Exploring Earth’s Most Speciated Insect Order

Books about Beetles

Unique pictorial atlases for identifying Beetles:

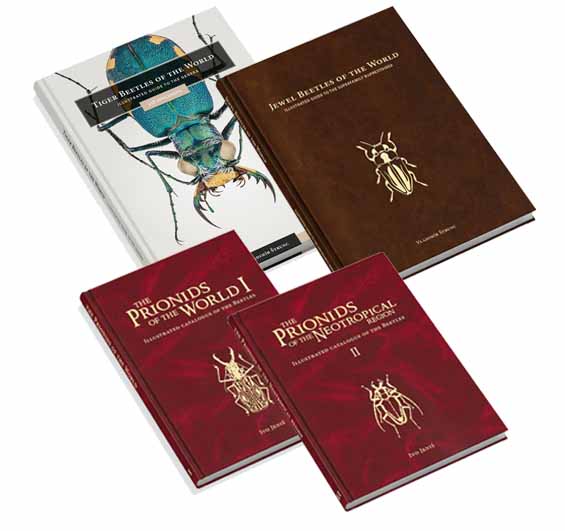

(2020) Tiger Beetles of the World, Cicindelidae, Illustrated guide to the genera

(2023) Tiger Beetles of Africa, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2024) Tiger Beetles of Orient, Cicindelidae, Geographical guide to the family Cicindelidae

(2022) Ground Beetles of Africa, Afrotropical Region

(2022) Jewel Beetles of the World, Buprestidae, Illustrated guide to the Superfamily Buprestoidea

(2008) The Prionids of the World, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

(2010) The Prionids of the Neotropical region, Prioninae, Illustrated catalogue of the Beetles

These remarkable creatures belong to the order Coleoptera, a name derived from Greek words meaning “sheath wings,” referring to their modified front wings that serve as protective covers. Most beetles share distinctive characteristics including a hard exoskeleton, strong mandibulate mouthparts, and a complete metamorphosis life cycle comprising egg, larva, pupa, and adult stages. Their extraordinary evolutionary success has enabled them to colonize virtually every terrestrial and freshwater habitat worldwide, developing specialized adaptations for countless ecological niches. This comprehensive exploration examines the classification, major families, distinctive features, and ecological significance of beetles, illuminating why these insects have become the most successful animal group in terms of species diversity.

Kinds of beetles insects

Evolutionary Classification of Coleoptera

The order Coleoptera represents the pinnacle of insect diversification, with modern classification systems recognizing more than 200 families of both extant and extinct beetles. This enormous group is divided into four primary suborders: Adephaga, Archostemata, Myxophaga, and Polyphaga, with the latter containing approximately 90 percent of all beetle species. The taxonomic structure of beetles is remarkably complex, with numerous superfamilies, families, subfamilies, tribes, and subtribes reflecting their evolutionary radiation into countless ecological niches. This hierarchical classification continues to evolve as researchers discover new species and relationships, with molecular techniques increasingly complementing traditional morphological approaches to beetle taxonomy.

For practical field identification, entomologists often focus on the two most prominent suborders with common families: Adephaga and Polyphaga. These can be distinguished by examining their first abdominal sternum – in Adephaga, this structure is divided by the hind coxae, while in Polyphaga, it remains undivided. This seemingly minor anatomical difference reflects deeper evolutionary divergences that occurred as beetles adapted to different lifestyles and habitats over millions of years. The extraordinary adaptability of beetles has allowed them to thrive through major geological and climatic changes that caused extinction in many other insect groups.

The evolutionary success of beetles stems largely from key innovations in their body plan, particularly their protective front wings (elytra) that shield their membranous flight wings and vulnerable abdomen. This adaptation provided exceptional protection against predators and harsh environmental conditions while maintaining the capacity for flight. Another critical factor in beetle diversification has been their complete metamorphosis life cycle, which allows different life stages to exploit different resources, effectively reducing competition between juveniles and adults of the same species. These advantages, combined with specialized mouthparts adapted for diverse feeding strategies, have enabled beetles to exploit ecological opportunities unavailable to other insect orders.

Remarkable Morphological Diversity

The morphological variation among beetle species is nothing short of astounding, with body sizes ranging from less than 1 millimeter in feather-winged beetles (Ptiliidae) to over 12 centimeters in some tropical species. This size spectrum, representing more than a hundred-fold difference, is accompanied by extraordinary variation in body shape, coloration, and specialized structures adapted for particular ecological roles or defensive strategies. Despite this diversity, beetles maintain certain defining characteristics that unite the order, most notably their hardened forewings (elytra) that typically meet in a straight line down the middle of the back when at rest. This distinctive feature provides immediate visual identification of the order even for non-specialists.

The coloration patterns exhibited by beetles are among the most varied and striking in the insect world, ranging from cryptic camouflage to bold aposematic warning signals advertising toxicity or distastefulness. Some species, like certain tortoise beetles studied by biologist Lynette Strickland, display remarkable intraspecific variation, with individuals of the same species exhibiting dramatically different colors and patterns. Her research on Chelymorpha alternans revealed that a range of beetles with appearances so distinct they were previously thought to represent different species – from red shells with black polka dots to metallic gold striped individuals – were actually members of a single species with high genetic diversity. This finding challenges traditional assumptions about species boundaries and highlights the complexity of color pattern development and evolution in beetles.

Beetles have evolved specialized appendages and body modifications for almost every conceivable ecological function, from the elongated snouts of weevils used for feeding and egg-laying to the elaborate horns of rhinoceros beetles used in male competition. Many species possess chemically defended glands that produce noxious compounds, while others have developed mechanical defenses such as the clicking mechanism in click beetles (Elateridae) that allows them to launch themselves into the air when threatened. Perhaps most remarkably, some beetle families like fireflies (Lampyridae) have evolved bioluminescent organs capable of producing species-specific flashing patterns used primarily for mate attraction and recognition. These diverse adaptations reflect the extraordinary evolutionary plasticity of the beetle body plan.

Major Beetle Families and Their Characteristics

Kinds of beetles insects

Ground-Dwelling Predators and Scavengers

Ground beetles (Carabidae) represent one of the most diverse and ecologically important beetle families, comprising predatory species that hunt on soil surfaces in forests, fields, and gardens worldwide. These beetles typically have long legs adapted for swift movement, powerful mandibles for capturing prey, and protective body armor that shields them from potential predators. Many ground beetles produce defensive chemical compounds when disturbed, creating an effective deterrent against vertebrate predators. Their ecological importance stems from their role as natural control agents for many invertebrate populations, particularly agricultural pests, making them valuable allies to farmers and gardeners implementing biological pest management strategies.

Carrion beetles or burying beetles (Silphidae) perform the essential ecological service of recycling dead animal matter back into the nutrient cycle. These fascinating insects can detect the odor of recently deceased small vertebrates from considerable distances, flying to corpses where mating pairs will cooperatively bury the carcass to serve as a protected food source for their developing larvae. This behavior not only accelerates decomposition processes but also reduces competition from flies and other scavenging insects. Some carrion beetle species exhibit remarkable parental care, with adults remaining to protect and even feed their developing young – a relatively uncommon behavior among insects. These beetles play a crucial role in forensic entomology, as their predictable arrival times at corpses help establish time of death in legal investigations.

Rove beetles (Staphylinidae) constitute one of the largest beetle families with over 63,000 species distributed across thousands of genera, making them among the most common beetles worldwide. Immediately recognizable by their shortened elytra that leave most of their flexible abdomen exposed, rove beetles have adapted to a wide range of habitats, though they are particularly abundant in moist, humid environments. Their colors span a remarkable spectrum from reddish-brown, red, and yellow to black and even iridescent green and blue, with sizes ranging from less than one millimeter to 35 millimeters, though most fall within the 2-7.6 millimeter range. These predominantly predatory beetles feed on smaller arthropods and decaying organic matter, playing significant roles in soil ecology and natural pest suppression in agricultural systems. kinds of beetle bugs, types of bugs

Plant-Associated Beetle Families

Weevils (Curculionoidea) represent one of the most specialized and diverse beetle groups, immediately recognizable by their elongated snouts housing their mouthparts. These distinctive “noses” serve multiple functions: they allow weevils to bore into plant tissues for feeding, create chambers for egg deposition, and in some species, function in male competition for mates. The approximately quarter-inch (6mm) body size of many weevil species belies their enormous ecological and economic impact, as many species are significant agricultural pests capable of devastating crops. However, some weevil species have been successfully employed as biological control agents against invasive plants, demonstrating their potential utility in ecological restoration efforts. Their specialized plant associations have driven remarkable co-evolutionary relationships with their host plants, resulting in high levels of host specificity.

Leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae) comprise a large family of predominantly herbivorous beetles that have evolved in close association with flowering plants, developing specialized adaptations for feeding on different plant tissues. Many species are strikingly colored with metallic or warning coloration, often sequestering plant toxins for their own defense against predators. The ecological impact of leaf beetles extends beyond direct plant consumption, as many species serve as vectors for plant diseases or create wounds that facilitate pathogen entry. Despite their primarily destructive reputation, leaf beetles fulfill important ecological functions including selective herbivory that influences plant community composition and structure. Some species have highly specialized relationships with particular plant families, making them useful bioindicators of habitat quality and plant diversity.

Longhorned beetles (Cerambycidae) are named for their exceptionally long antennae that often exceed the length of their bodies and serve crucial sensory functions in locating suitable host trees. These primarily wood-boring beetles play vital roles in forest ecosystems as agents of dead wood decomposition, creating channels that accelerate the breakdown of woody material and facilitate fungal colonization. The larvae of most species develop inside wood, creating distinctive galleries that weaken structural timber and can cause significant economic damage in forestry and lumber industries. Adult longhorned beetles often feed on flowers, fruits, or foliage, with some species serving as pollinators for certain plant species. Their lifecycle, which can span several years in larger species, makes them particularly vulnerable to forest management practices that remove dead and dying trees.

Specialized Ecological Niches

Lady beetles or ladybugs (Coccinellidae) represent one of the most beloved and recognized beetle families, with over 5,000 species worldwide ranging in size from 0.8 to 18 millimeters. Despite their popular association with red bodies and black spots, lady beetles actually display remarkable color diversity including orange, yellow, black, grey, and brown varieties with various patterns. These beneficial insects have an omnivorous diet that includes fungus, plant material, and most importantly, agricultural pests such as aphids and scale insects, making them valuable allies in both organic and conventional agriculture. Their ability to consume large quantities of plant-feeding pests has led to their deliberate introduction as biological control agents in many parts of the world. Though most species are beneficial, some lady beetle species have become invasive when introduced outside their native range, demonstrating the ecological complexities of even well-intentioned biological control efforts.

Scarab beetles (Scarabaeidae) include the culturally significant dung beetles, which perform the essential ecological service of removing and burying animal waste. By breaking down dung and incorporating it into the soil, these beetles improve soil fertility, reduce parasite transmission, and accelerate nutrient cycling in both natural and agricultural ecosystems. Beyond their waste management services, scarab beetles include the charismatic rhinoceros and hercules beetles prized by collectors for their impressive horns used in male competitions. The religious significance of certain scarab beetles, particularly in ancient Egyptian culture where they symbolized rebirth and regeneration, demonstrates their profound cultural impact throughout human history. Their complex behaviors, including elaborate nesting strategies and in some species, parental care, reflect sophisticated adaptations to specialized ecological niches.

Dermestid or flesh-eating beetles (Dermestidae) possess the remarkable ability to digest keratin, a protein found in hair, feathers, and skin that few other organisms can break down. This specialized dietary adaptation makes them important decomposers in natural ecosystems and valuable tools in museum taxonomy, where they are used to clean skeletons by removing remaining tissue from bones. These beetles measure between 10-25 millimeters and range in coloration from red to brown and black, typically with elongated body forms adapted for navigating through hair and feathers. Found naturally on decomposing bodies that have been decaying for weeks, dermestid beetles also occasionally infest homes where they may damage natural fiber products. Their thorough consumption of animal remains speeds decomposition processes and facilitates the return of nutrients to ecological cycles, demonstrating their important role in ecosystem functioning.

Aquatic and Semi-Aquatic Beetles

Predaceous diving beetles (Dytiscidae) represent one of the most successful adaptations of the beetle body plan to fully aquatic environments, with streamlined shapes and specialized swimming legs that enable efficient movement through water. These predominantly predatory beetles hunt underwater, capturing other aquatic invertebrates, small fish, and amphibians using powerful mandibles and digestive enzymes. Despite their aquatic lifestyle, adult diving beetles retain functional wings and can fly between water bodies, allowing them to colonize temporary habitats and escape deteriorating conditions. They breathe underwater by trapping air bubbles beneath their elytra, effectively creating a physical gill that enables extended submersion. Their larvae, often called “water tigers,” are voracious predators with hollow, sickle-shaped mandibles used to inject digestive enzymes into prey and then extract the liquefied tissues.

Whirligig beetles (Gyrinidae) are immediately recognizable by their characteristic swimming behavior, rapidly circling on water surfaces in groups, which has earned them their common name. These social beetles possess divided eyes—a unique adaptation allowing them to simultaneously view the world above and below the water surface, providing vigilance against predators from multiple environments. Their streamlined bodies and paddle-like middle and hind legs enable efficient movement across water surfaces, while their front legs are modified for capturing prey. When disturbed, whirligig beetles can rapidly dive beneath the water surface, carrying air bubbles with them to breathe while submerged. Their social aggregations may provide protection against predators through dilution effects and collective vigilance, demonstrating sophisticated behavioral adaptations to their specialized ecological niche.

Water scavenger beetles (Hydrophilidae) fulfill important ecological functions as aquatic decomposers, feeding primarily on decaying plant material and small organisms in freshwater habitats. Unlike their predatory counterparts, these beetles typically have more rounded body forms and longer maxillary palps (sensory appendages) that are sometimes mistaken for antennae. Many species carry air bubbles beneath their bodies, using surface tension to create a physical gill for underwater respiration, though they must periodically return to the surface to replenish their air supply. Their larvae contrast with the adults by being primarily predatory, highlighting the ecological flexibility that complete metamorphosis provides. Some species have developed specialized adaptations for living in extreme aquatic environments, including highly polluted waters or temporary pools, demonstrating the remarkable adaptability of the beetle body plan.

Ecological Significance and Importance of Beetle Diversity

The ecological functions performed by beetles are as diverse as their morphology, with different species serving as herbivores, predators, parasites, decomposers, and pollinators across virtually all terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems. This functional diversity makes beetles integral to numerous ecological processes, including nutrient cycling, soil formation, waste decomposition, and population regulation of other organisms. Dung beetles alone save the cattle industry billions of dollars annually by removing animal waste that would otherwise foster parasites and disease while simultaneously improving soil fertility and structure. Predatory beetles provide essential biological control of potential pest species, while wood-boring beetles accelerate dead wood decomposition, creating habitat for other organisms and returning nutrients to forest soils.

Research by biologists like Lynette Strickland on tortoise beetles demonstrates that beetle diversity extends beyond simple species counts to encompass remarkable variation within species. Her genomic studies revealed that beetles with dramatically different appearances—from red shells with black polka dots to metallic gold stripes—belonged to a single species (Chelymorpha alternans) with high genetic diversity. This finding raises fascinating questions about the evolutionary forces maintaining such variation and challenges traditional approaches to defining species boundaries based primarily on appearance. Strickland’s research suggests that understanding the importance of variation in nature could provide insights relevant not only to biology but also to human social dynamics, where superficial differences often lead to arbitrary divisions despite our shared genetic heritage.

As the largest order of insects representing approximately 40 percent of all known insect species, beetles serve as excellent subjects for studying biodiversity patterns and conservation priorities. Their presence in virtually all habitats makes them valuable bioindicators, with beetle community composition often reflecting environmental conditions and disturbance histories. Many specialized beetle species have narrow habitat requirements, making them particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and fragmentation. Climate change poses additional challenges for beetle conservation, potentially disrupting the synchronization between beetle life cycles and those of their host plants or prey. Understanding and preserving beetle diversity thus represents an important component of broader conservation efforts aimed at maintaining ecosystem health and resilience in a changing world.

Conclusion

Kinds of beetles insects

The order Coleoptera exemplifies the extraordinary adaptive potential of the insect body plan, with beetles having evolved specialized adaptations for countless ecological niches over hundreds of millions of years. From the beneficial ladybugs that control agricultural pests to the efficient waste recycling performed by dung beetles, and from the wood-decomposing activities of longhorned beetles to the bioluminescent displays of fireflies, beetles demonstrate the intricate connections between biodiversity and ecosystem function. Their remarkable success—representing approximately 40 percent of all insect species and 25 percent of all animal species—testifies to the evolutionary advantages provided by their distinctive characteristics, particularly their protective elytra and complete metamorphosis lifecycle.

The study of beetle diversity continues to yield new insights into evolutionary processes, ecological relationships, and conservation priorities. New species are regularly discovered, even in well-studied regions, suggesting that current estimates of beetle diversity likely underestimate their true numbers. As human activities increasingly threaten natural habitats worldwide, understanding and preserving beetle diversity becomes not merely an academic pursuit but an essential component of maintaining healthy, functioning ecosystems. The lessons we learn from studying these extraordinarily successful insects may provide valuable guidance for addressing the broader biodiversity crisis facing our planet, reminding us that even small organisms can have profound ecological importance. Bug Identification