Longhorn Beetles (Cerambycidae, Coleoptera)

Comprehensive Overview of the Longhorn Beetle Family

1. Introduction to Cerambycidae (Longhorn Beetles)

1.1 Taxonomic Position and Family Characteristics

The family Cerambycidae, commonly known as longhorn beetles or longicorn beetles, represents one of the most conspicuous and readily recognizable groups within the order Coleoptera. Members of this family are characterized by their exceptionally long, thread-like antennae, which in many species exceed body length, sometimes by several times. The family name derives from the Greek kerambyx, referring to a wood-boring beetle.

Classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Coleoptera

Suborder: Polyphaga

Infraorder: Cucujiformia

Superfamily: Chrysomeloidea

Family: Cerambycidae Latreille, 1802

Cerambycidae primarily inhabit forested and shrubland habitats, though numerous species occur in cultural landscapes, orchards, parks, and urban environments. For entomologists, foresters, and nature enthusiasts, this family represents an extraordinarily diverse group of significant importance for biodiversity, woody plant ecology, and forest ecosystem health.

Types Subfamily Prioninae

1.2 Global Diversity and Species Richness

The family Cerambycidae is remarkably diverse, with over 35,000 described species worldwide distributed across approximately 4,000 genera. New species continue to be discovered and described regularly, particularly in tropical regions where diversity is highest. The family ranks among the largest within Coleoptera and represents a substantial component of saproxylic beetle fauna globally.

Regional Diversity:

- Neotropical region: ~13,000-15,000 species (highest diversity)

- Oriental region: ~8,000-10,000 species

- Palearctic region: ~3,500-4,000 species

- Nearctic region: ~1,000-1,200 species

- Afrotropical region: ~5,000-6,000 species

- Australasian region: ~2,500-3,000 species

In Europe, approximately 800-900 species are recorded, with several dozen representing common elements of the fauna, while many others are rare, threatened, or restricted to specific habitat types. Central Europe, including the Czech Republic, hosts approximately 200-250 species.

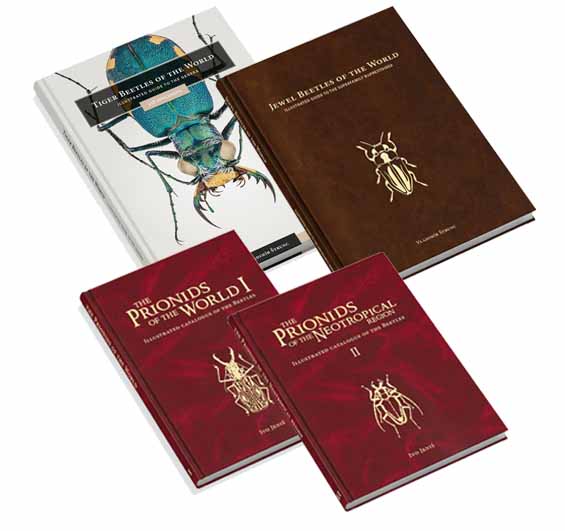

This extraordinary species richness makes Cerambycidae a frequent subject of identification guides, faunal atlases, and specialized monographs. Serious study of the family requires quality literature and comprehensive educational materials enabling rapid comparison of morphological characters across genera and species.

1.3 Subfamilies and Major Taxonomic Groups

Cerambycidae is traditionally divided into several subfamilies, though taxonomic arrangements continue to evolve with molecular phylogenetic research:

Major Subfamilies:

- Prioninae – Primitive longhorns, generally large-bodied with robust mandibles and serrate or flabellate antennae. Includes genera such as Prionus, Ergates, Aegosoma, and Tragosoma.

- Lepturinae – Flower longhorns, typically found on flowers, often with narrowed, tapering elytra. Important genera include Leptura, Strangalia, Anastrangalia, and Grammoptera.

- Cerambycinae – True longhorns, diverse in size and ecology, including many economically important species. Major genera include Cerambyx, Aromia, Rosalia, Hylotrupes, and Trichoferus.

- Lamiinae – Flat-faced longhorns, characterized by vertical frons (face), often robust-bodied. Includes Monochamus, Lamia, Saperda, Tetrops, and Oberea.

- Spondylidinae – Small subfamily of primarily conifer-associated species, including Spondylis and Tetropium.

Additional smaller subfamilies include Necydalinae, Parandrinae, and Vesperinae, among others. This classification system provides a framework for organizing the family’s vast diversity and aids in identification and ecological study.

2. Diagnostic Morphological Characters of Cerambycidae

2.1 General Body Structure and Habitus

Cerambycids exhibit a characteristic body form that, with practice, enables relatively straightforward recognition. The basic body shape is elongate, typically cylindrical to somewhat dorsoventrally flattened. The head is distinctly separated from the thorax and often slightly inclined downward, creating a characteristic “tucked” profile when viewed laterally.

General Proportions:

- Body length varies from 2-3 mm in smallest species to over 170 mm in tropical giants (Titanus giganteus)

- European species typically range 3-60 mm

- Czech fauna includes species 2-55 mm

The thorax (pronotum) is robust and may be smooth, armed with lateral spines, tubercles, or carinate margins depending on the taxon. The abdomen is covered by elytra of variable length—in most species extending to the abdominal apex, though in some groups (particularly Necydalinae and some Lepturinae) elytra may be abbreviated, exposing terminal abdominal segments.

2.2 Antennae – The Defining Character

The most conspicuous and reliable diagnostic character of Cerambycidae is the presence of remarkably elongate antennae. In many species, antennae exceed body length, sometimes by two to three times or more. Antennae are multisegmented (typically 11 segments, occasionally 12 in some Prioninae), often finely pubescent or bearing short setae, with some species displaying distinctly thickened or contrastingly colored segments.

Antennal Variations:

- Length: Variable from slightly shorter than body to 3-4× body length

- Insertion: Typically within antennal notches of compound eyes

- Sexual dimorphism: Males generally possess longer antennae than females

- Segment modifications: May be serrate, flabellate, clubbed, or simple

- Setation: Dense pubescence or long erect setae in some taxa

Antennal shape, segmentation pattern, and proportions serve as critical identification characters in taxonomic keys and are essential for generic and specific determination.

2.3 Head Morphology

The head capsule exhibits several taxonomically important features:

Key Characters:

- Frons orientation: Vertical (Lamiinae) versus oblique or horizontal (most other subfamilies)

- Antennal tubercles: Prominence and spacing

- Compound eyes: Shape varies from entire to deeply emarginate (kidney-shaped)

- Lower eye lobes: Present in many taxa where eyes are divided by antennal insertion

- Mandibles: Size, shape, and sexual dimorphism

- Gular sutures: Presence/absence and convergence pattern

The degree of eye emargination, where antennae are inserted within deep notches creating divided upper and lower eye lobes, is particularly important in subfamily classification.

2.4 Pronotum Structure and Armature

The pronotum (dorsal surface of the prothorax) provides numerous diagnostic characters:

Shape and Proportions:

- Width relative to length (transverse, quadrate, elongate)

- Lateral margins (rounded, angulate, spinose)

- Basal and apical constrictions

- Dorsal convexity or flattening

Surface Features:

- Sculpturing: punctation, granulation, rugosity

- Carinae or costae (ridges)

- Tubercles or gibbosities

- Lateral spines or teeth (number, position, development)

- Pubescence pattern and density

In Prioninae, the number and prominence of lateral pronotal teeth is a key generic character. The pronotum may be smooth and polished in some taxa (Rosalia, Cerambyx) or densely sculptured and setose in others.

2.5 Elytra – Structure, Sculpture, and Ornamentation

The elytra (wing cases) provide extensive taxonomic information:

Structural Features:

- Length and width relative to body

- Shape: parallel-sided, tapering, dilated

- Humeral angles: prominent versus rounded

- Apices: rounded, truncate, emarginate, spinose, dehiscent

- Sutural margin relationship

Surface Characteristics:

- Longitudinal costae (ridges) or striae

- Punctation pattern and density

- Rugosity, granulation, or reticulation

- Pubescence: color, density, pattern

- Scales or specialized setae

Ornamentation:

- Color pattern: uniform, banded, mottled, fasciate

- Contrasting pubescent patches

- Metallic luster or iridescence

- Mimetic patterns (wasp/bee mimicry)

The elytral apex morphology is particularly important in Lepturinae, where species may have rounded, truncate, spinose, or deeply emarginate apices.

2.6 Legs and Tarsal Structure

Leg morphology provides subfamily-level and sometimes generic characters:

Femoral Characteristics:

- Shape: linear, clavate (club-shaped), pedunculate

- Armature: spines, teeth, or smooth

- Relative proportions among fore, middle, and hind legs

Tibial Features:

- Curvature and relative length

- Apical spurs: number and development

- Corbels or excavations for tarsal reception

- Armature and pubescence

Tarsal Formula: Cerambycidae possess a 5-5-5 tarsal formula (actually pseudotetramerous 5-5-4 in appearance), with segment 4 typically bilobed or concealed. The third tarsomere is typically deeply bilobed, with segment 4 small and inserted between lobes. This character helps distinguish Cerambycidae from some superficially similar families.

Tarsal Claws:

- Simple versus appendiculate

- Presence of basal teeth

- Divergence and relative size

2.7 Ventral Morphology

Ventral characters, though requiring specimen manipulation, provide valuable taxonomic information:

Prosternal Process:

- Width and shape

- Apical expansion or truncation

- Relationship to mesocoxae

Mesosternum and Metasternum:

- Intercoxal process width

- Sculpturing and pubescence

- Presence of grooves or carinae

Abdominal Sternites:

- Number visible (typically 5)

- Shape of terminal sternite

- Presence of sexual characters

- Punctation and pubescence patterns

2.8 Coloration and Mimicry

Cerambycid coloration ranges from cryptic to aposematic:

Cryptic Coloration: Many species, particularly those active on bark or in cryptic habitats, exhibit browns, grays, and mottled patterns perfectly matching tree bark, lichen-covered wood, or dead branches. This includes many Prioninae and bark-dwelling Lamiinae.

Aposematic and Mimetic Patterns: Numerous species display striking yellow-and-black or orange-and-black banding patterns mimicking aculeate Hymenoptera (wasps, bees). Notable examples include:

- Clytus arietis – wasp beetle, remarkably wasp-like

- Chlorophorus species – banded patterns

- Plagionotus species – yellow-banded

- Rutpela maculata – spotted flower longhorn

Metallic Coloration: Some species exhibit brilliant metallic colors:

- Aromia moschata – metallic green/blue musk beetle

- Rosalia alpina – blue-gray with black bands

- Various tropical Sternotomis and Tmesisternus species

Warning Coloration: Species that sequester defensive compounds or possess effective chemical defenses may display bright, contrasting patterns warning potential predators.

2.9 Sexual Dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is pronounced in many cerambycids:

Common Dimorphic Characters:

- Antennal length: Males typically with longer antennae

- Body size: Females often larger and more robust

- Mandible development: Males with larger, more curved mandibles (especially Prioninae)

- Abdominal sternites: Males with modified terminal sternites

- Leg proportions: Variable, sometimes males with elongated forelegs

- Coloration: Occasionally differing between sexes

Recognition of sexual dimorphism is essential for accurate species identification and ecological studies.

2.10 Larval Morphology

Cerambycid larvae, colloquially called “roundheaded wood borers,” exhibit characteristic morphology:

General Structure:

- Elongate, cylindrical body

- Well-developed, heavily sclerotized head capsule

- Reduced or absent thoracic legs (varies by subfamily)

- Expanded thoracic segments, particularly prothorax

- Pale coloration: white, cream, or yellowish

Diagnostic Characters:

- Head capsule: Dark, robust, with powerful mandibles

- Thoracic segments: Dorsoventrally flattened, broader than abdomen

- Ambulatory ampullae: Dorsal and ventral swellings bearing minute asperities

- Spiracles: Typically annular-biforous

- Urogomphi: Usually absent (distinguishes from most Buprestidae)

Larval Galleries and Frass: Larvae create characteristic galleries in wood:

- Gallery shape: Oval to flattened in cross-section

- Frass type: Coarse, fibrous wood particles (versus fine powder)

- Gallery packing: Loosely to tightly packed depending on species

- Orientation: May follow or cross wood grain

Larval determination to species is challenging, often requiring detailed morphological study, molecular techniques, or rearing to adult stage. Specialized literature with detailed larval descriptions and illustrations is essential for this work.

3. Biology and Life Cycle of Cerambycidae

3.1 General Biological Characteristics

Cerambycidae represents an extraordinarily diverse family with thousands of species worldwide, united by elongate body form and characteristically long antennae. Most species are intimately associated with woody plants—living trees, dead wood, or fallen logs. This association with wood fundamentally influences their biology, ecology, and practical significance in forestry and conservation.

Adult cerambycids are predominantly diurnal or crepuscular, though some species exhibit primarily nocturnal activity. They possess well-developed olfaction enabling location of suitable host trees, often preferring weakened, freshly cut, or mechanically damaged material. Many species are attracted to volatile compounds released from fresh wood or sap flows, a characteristic exploited in field collection using baits and attractants.

3.2 Reproductive Biology and Mating Systems

Mate Location: Males employ various strategies to locate females:

- Pheromone detection: Many species use long-distance sex pheromones produced by females

- Host plant volatiles: Aggregation at suitable breeding material

- Visual searching: Active patrolling of host plants or flowers

- Acoustic signals: Some species produce stridulatory sounds

Mating Behavior: Mating occurs on host plants, flowers, or breeding substrates. Copulation may last from minutes to several hours. Males of some species exhibit aggressive competition, using enlarged mandibles to displace rivals or guard females.

Reproductive Strategies:

- Iteroparity: Multiple mating opportunities for both sexes

- Sperm competition: Mechanisms to ensure paternity

- Mate guarding: Males may remain with females post-copulation

3.3 Egg Stage – Initiation of the Life Cycle

The life cycle begins with oviposition on or into suitable host material. Females actively search for appropriate substrates using visual, olfactory, and possibly tactile cues.

Oviposition Sites:

- Bark crevices and fissures

- Wounds and damaged areas

- Cut stumps and fresh logging debris

- Existing beetle emergence holes

- Root collars and soil interface

- Herbaceous stems (some Lamiinae)

Egg Characteristics:

- Shape: Elongate-oval to cylindrical

- Color: White to cream-colored

- Size: Typically 2-6 mm length

- Protection: Often coated with secretions or surrounded by chewed wood particles

Fecundity: Egg production varies widely:

- Small species: 20-50 eggs

- Medium-sized species: 50-200 eggs

- Large species: 200-400+ eggs

Eggs are typically laid singly or in small groups. Females may distribute eggs across multiple host individuals to reduce intraspecific competition and predation risk.

Embryonic Development: Duration depends on temperature and humidity:

- Optimal conditions: 1-3 weeks

- Cooler conditions: 3-6 weeks

- Embryonic diapause possible in some species

3.4 Larval Stage – The Wood-Boring Phase

The larval stage represents the longest and ecologically most significant phase of cerambycid development.

Larval Behavior and Feeding:

Upon hatching, neonate larvae immediately bore into host material. Initial feeding occurs in phloem and cambial tissues, with larvae progressively penetrating deeper into sapwood and occasionally heartwood as they develop.

Gallery Construction:

- Initial galleries: Narrow, winding, following nutritious tissues

- Later instars: Broader, more irregular galleries

- Cross-section: Oval to flattened, reflecting larval body shape

- Packing: Frass loosely to tightly packed depending on species and substrate

Feeding Ecology:

Cerambycid larvae are primarily xylophagous (wood-feeding), though nutritional strategies vary:

- Fresh wood feeders: Attack recently dead or dying trees

- Moderately decayed wood specialists: Require partial fungal decomposition

- Advanced decay specialists: Feed in highly degraded wood

- Heartwood borers: Penetrate sound heartwood

- Sapwood specialists: Remain in outer wood layers

- Bark/phloem feeders: Some species complete development beneath bark

Nutritional Physiology:

Wood is nutritionally poor, consisting primarily of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin with low nitrogen content. Larvae overcome this through:

- Symbiotic microorganisms: Bacterial and fungal endosymbionts in gut aid digestion

- Fungal associations: Many species cultivate or exploit wood-decay fungi

- Nitrogen recycling: Uric acid resorption and microbial nitrogen fixation

- Extended development: Long larval periods allow accumulation of necessary nutrients

Developmental Duration:

Larval development time varies dramatically:

- Rapid developers: 1 year (some small species, tropical environments)

- Typical development: 2-3 years (temperate zone species)

- Extended development: 3-5 years (large species, cold climates, hard wood)

- Exceptional cases: 10+ years reported for some Prioninae in extreme conditions

Instar Number:

Most species undergo 8-15 larval instars, though precise numbers are difficult to determine due to prolonged, asynchronous development. Larger species generally have more instars than smaller species.

Overwintering:

In temperate regions, larvae overwinter in wood, entering dormancy during coldest months. Some species may experience multiple winters before completing development.

3.5 Pupal Stage – Metamorphosis

Prepupal Chamber Construction:

Mature larvae prepare for pupation by constructing specialized chambers:

- Location: Typically near wood surface (5-50 mm depth)

- Orientation: Usually parallel to wood grain

- Shape: Oval chamber slightly larger than pupa

- Lining: May be smooth or lined with fine wood particles

- Closure: Often sealed with wood particles and frass

Timing:

Pupation timing is species-specific and synchronized with adult emergence periods:

- Spring emergers: Pupate late winter to early spring

- Summer emergers: Pupate spring to early summer

- Facultative diapause: Some species may delay pupation

Pupal Characteristics:

Cerambycid pupae are exarate (free-limbed) with appendages clearly visible:

- Coloration: Initially pale white to yellowish

- Development: Progressive darkening as adult pigmentation develops

- Duration: 2-6 weeks depending on species and temperature

- Vulnerability: Immobile stage susceptible to predation and environmental stress

Adult Maturation:

Newly eclosed adults (teneral stage) remain in pupal chamber for days to weeks, allowing:

- Cuticle sclerotization and hardening

- Development of final coloration

- Resorption of pupal remains

- Maturation of reproductive organs

3.6 Adult Stage – Dispersal and Reproduction

Emergence:

Adults excavate exit tunnels to wood surface, creating characteristic emergence holes:

- Hole shape: Circular to oval, matching body cross-section

- Diameter: Species-specific, 2-20+ mm

- Location: Variable – may be far from pupal chamber

- Timing: Often synchronized with favorable weather

Adult Phenology:

Adult activity periods are species-specific:

- Spring species: April-June (e.g., Rhagium, Gaurotes)

- Early summer species: May-July (e.g., Leptura, Grammoptera)

- Midsummer species: June-August (e.g., Cerambyx, Aromia)

- Late summer species: July-September (e.g., Monochamus, some Saperda)

Some species have extended or multiple emergence peaks within a season.

Adult Feeding:

Adult feeding behavior varies:

- Nectar and pollen feeders: Many Lepturinae are anthophilous (flower-visiting)

- Sap feeders: Some species feed on tree sap flows

- Foliage feeders: Certain Lamiinae consume leaves, shoots, or bark

- Minimal feeding: Many Prioninae and some others feed little or not at all as adults

- Maturation feeding: Some species require feeding for reproductive development

Adult Longevity:

Adult lifespan varies:

- Short-lived species: 1-3 weeks (many Prioninae)

- Typical longevity: 2-8 weeks

- Long-lived species: Several months possible in some taxa

3.7 Voltinism and Life Cycle Duration

Voltinism Patterns:

- Univoltine: One generation per year (rare in temperate cerambycids)

- Semivoltine: One generation per 2-3 years (typical for many species)

- Prolonged development: 3-5+ years per generation (large species, cold climates)

Factors Affecting Development Rate:

- Temperature: Primary determinant of development speed

- Host wood quality: Nutritional value affects growth rate

- Wood moisture: Influences fungal colonization and larval survival

- Wood density/hardness: Harder woods extend development time

- Decay stage: Some species require specific decomposition states

- Larval density: Intraspecific competition may slow development

- Geographic location: Latitude and elevation affect development duration

Life Cycle Synchronization:

Many species exhibit synchronized adult emergence through:

- Environmental cues: Temperature thresholds, photoperiod

- Pheromonal synchronization: Chemical signals coordinate emergence

- Resource availability: Timing matched to host plant phenology

3.8 Ecological Significance of Life History Traits

The prolonged life cycles and wood-dependent development of cerambycids have important ecological implications:

Deadwood Dependency: Long larval development requires deadwood persistence, making cerambycids sensitive to forestry practices removing deadwood.

Population Dynamics: Multi-year development creates overlapping generations and buffered population dynamics, but also increases vulnerability to habitat disturbance.

Dispersal Limitations: Long development periods may limit ability to track rapidly changing environments or colonize newly available habitats.

Conservation Implications: Understanding life cycle duration is critical for:

- Assessing population viability

- Designing effective monitoring programs

- Implementing appropriate management interventions

- Predicting responses to environmental change

4. Distribution and Habitats of Cerambycidae Globally and in the Czech Republic

4.1 Global Distribution Patterns

Cerambycidae exhibit a nearly cosmopolitan distribution, occurring on all continents except Antarctica. The family has successfully radiated into diverse habitats from tropical rainforests to boreal coniferous forests, from sea level to high mountain elevations.

Latitudinal Diversity Gradient:

Species richness follows a pronounced latitudinal gradient with highest diversity in tropical regions:

- Tropics (0-23°): 60-70% of global cerambycid diversity

- Subtropics (23-35°): 15-20% of species

- Temperate zones (35-60°): 10-15% of species

- Boreal regions (>60°): <5% of species

Centers of Diversity:

Neotropical Region:

- Amazon Basin: Highest diversity globally

- Atlantic Forest: High endemism

- Andean cloud forests: Specialized montane fauna

- Brazilian cerrado: Distinct savanna-adapted species

Oriental Region:

- Southeast Asian rainforests: Exceptionally diverse

- Indo-Malayan archipelago: Island endemics

- Himalayan forests: Diverse montane fauna

Afrotropical Region:

- Congo Basin: High diversity but poorly studied

- Eastern Arc Mountains: Endemic species

- Madagascar: Unique endemic fauna

Palearctic Region:

- Mediterranean Basin: Refugial diversity

- Temperate deciduous forests: Moderate diversity

- Boreal taiga: Lower diversity but ecologically important species

Australasian Region:

- Queensland rainforests: High diversity

- New Guinea: Poorly explored diversity

- New Zealand: Depauperate fauna

4.2 Habitat Types and Ecological Requirements

4.2.1 Forest Habitats

Primary Old-Growth Forests:

These represent optimal habitat for many cerambycid species, particularly rare and threatened specialists:

- Key features:

- High volume of deadwood in various decay stages

- Structural complexity (canopy gaps, varied age classes)

- Continuity of deadwood supply over time

- Presence of veteran trees with rot cavities

- Diverse tree species composition

- Characteristic taxa:

- Rosalia alpina – requires large-diameter beech deadwood

- Cerambyx cerdo – associated with ancient oaks

- Aegosoma scabricorne – old-growth beech and oak specialist

- Many specialized Lamiinae requiring specific fungal-colonized wood

Managed Production Forests:

Commercial forests support cerambycid communities when management incorporates:

- Retention of deadwood volumes (>20 m³/ha recommended)

- Varied rotation lengths creating age diversity

- Retention of individual veteran trees

- High stumps and logging residues left on site

- Reduced salvage logging intensity

Specific Forest Types:

- Broadleaved Deciduous Forests:

- Oak forests (Quercus spp.)

- Beech forests (Fagus spp.)

- Oak-hornbeam forests (Carpinion)

- Mixed thermophilous forests

- Important genera: Cerambyx, Plagionotus, Saperda, Phymatodes

- Coniferous Forests:

- Spruce forests (Picea abies)

- Pine forests (Pinus sylvestris, P. mugo)

- Fir forests (Abies alba)

- Mixed montane coniferous forests

- Key taxa: Monochamus, Tetropium, Rhagium, Spondylis, Tragosoma

- Mixed Forests:

- Provide highest overall diversity

- Support both conifer and broadleaf specialists

- Edge effects create microhabitat diversity

- Riparian and Floodplain Forests:

- Dynamic environments with frequent disturbance

- Regular deadwood creation through flooding

- Willow (Salix), poplar (Populus), alder (Alnus) specialists

- Genera: Aromia, Lamia, Oberea, Saperda

4.2.2 Non-Forest Habitats

Wood-Pastures and Parklands: Traditional agro-forestry systems supporting exceptional cerambycid diversity:

- Ancient trees with rot cavities and deadwood

- Open-grown trees with sun-exposed deadwood

- Continuity of veteran tree populations

- Important for Cerambyx, Plagionotus, Saperda spp.

Orchards and Fruit Tree Plantations:

- Traditional extensively managed orchards are important

- Aging apple, pear, plum, cherry trees

- Deadwood in crowns and limbs

- Species: Cerambyx scopolii, Saperda spp., Phytoecia spp.

- Intensive modern orchards have minimal value

Urban and Suburban Habitats:

- Parks with mature trees

- Historic gardens and estates

- Cemetery trees

- Street tree allees

- Can serve as refugia in intensively managed landscapes

Steppe and Open Woodland:

- Thermophilous species adapted to:

- Sun-exposed deadwood

- Scattered shrubs and small trees

- Dry, warm microclimates

- Genera: Dorcadion, Deilus, Phytoecia, Agapanthia

Alpine and Subalpine Zones:

- Specialized montane fauna

- Dwarf pine (Pinus mugo) associates

- Larch and stone pine specialists

- Genera: Rosalia, Rhagium, montane Leptura spp.

4.3 European Distribution and Biogeographic Regions

Europe hosts approximately 800-900 cerambycid species with uneven distribution across biogeographic regions.

Mediterranean Region:

- Highest diversity in Europe (400+ species)

- Many endemic and relict species

- Thermophilous oak specialists

- Sclerophyllous woodland fauna

- Important genera: Cerambyx, Purpuricenus, Parmena, Ropalopus

Atlantic Region:

- Moderate diversity

- Oceanic climate specialists

- Ancient broadleaved woodland species

- Declining due to intensive agriculture

Continental Region:

- Central European core

- Diverse forest types supporting varied fauna

- Mix of thermophilous and cold-adapted species

- Important conservation areas: Carpathians, Alps foothills

Pannonian Region:

- Steppe-forest mosaic

- Thermophilous open woodland species

- Ancient tree specialists in lowland forests

Alpine Region:

- Montane and subalpine specialists

- Reduced diversity but high endemism

- Important genera: Rosalia, montane Leptura, Rhagium

Boreal Region:

- Lower diversity

- Conifer specialists predominate

- Circumpolar species

- Genera: Monochamus, Tetropium, Rhagium, Tragosoma